The white-bellied frog (Anstisia alba) is not only one of Australia’s tiniest amphibians, but also one of its most endangered. And yet, against the odds, a quiet revolution is unfolding – where mud-splattered scientists, solar-powered sprinklers, satellite technology and a partnership between government and a grassroots organisation are coming together to give this tiny survivor, and others like it, a fighting chance.

When you think about the life cycle of a frog, it’s natural to imagine a beginning where eggs laid in water eventually hatch into tadpoles, followed by a metamorphosis over weeks where they turn into frogs.

Not so for the critically endangered, white-bellied frog (Anstisia alba). Found only within a very limited distribution near Margaret River, it lays its eggs not into water, but into a shallow, muddy creek burrow. The resulting tadpoles live within the egg before eventually hatching as a fully formed and Rice Bubble-sized baby frog.

Only discovered in the early 1980s, the tiny amphibian has captivated environmental scientists for decades. Around 30 years of comprehensive monitoring data exists as Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA) staff and university student researchers have worked tirelessly over the years (sometimes up to their elbows in mud at night) to coax this diminishing species back from the brink of extinction.

A recovery plan for the species was first prepared in 1994 and a new revised version adopted in 2015. While the dataset and associated knowledge base have continued to expand, conservation progress has struggled to gain a foothold, bracing against the rising tide of climate change combined with increasingly stretched public resources.

PREVENTING EXTINCTION

The white-bellied frog is just one of more than 1,700 threatened species in Australia and one of 110 listed for priority attention in the Australian Government’s Threatened Species Action Plan 2022-2032 - Towards Zero Extinctions.

Australia has one of the highest loss of species anywhere in the world with 100 of the country’s endemic species becoming extinct since colonisation. A lot hangs on this action plan.

Every year, more species are added to the IUCN list of threatened species, along with an increasing number and intensity of threats to their survival, from climate change to reduced habitat to introduced predators. As a community, Australia is grappling with how best to navigate this unchartered territory and we’re not alone; it’s happening across the world.

WHAT’S HAPPENING OVERSEAS

One Australian who has worked in threatened species conservation for more than 30 years and studied how these challenges are being addressed in many parts of the world is South West NRM CEO, Dr Manda Page.

In 2022, Dr Page undertook a Churchill Fellowship to explore, review and document international case studies of successful public-private partnerships that benefited threatened fauna with a view to identifying successful models and pitfalls to avoid.

In 64 days, she travelled 63,201 kilometres, visiting eight countries, and 15 national parks and reserves. She interviewed representatives from private, non-profit, non-government and government organisations achieving international success stories like the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund and its Ellen Degeneres Campus in Rwanda.

What she saw was non-government organisations equipped with various funding models really standing up and stepping in to help address the challenge – particularly in developing countries where governments are especially under-resourced for investing in the environment.

“Historically the public sector has assumed much of the burden of responsibility for threatened species recovery,” Dr Page said in her report. “However private, non-profit, non-government organisations dedicated to conservation are increasing.”

THE PARTNERSHIP APPROACH

Two years after publishing the report – from the unique career position where she now sits having worked in environmental conservation both within and outside of government and across two Australian states – Dr Page remains resolute. No longer can governments alone deliver environmental conservation outcomes, and moving further toward a more partnership-based approach is critical to achieving progress.

But are there partners capable of stepping in to help bridge the gap? In WA, Dr Page says that is still a work in progress, but she can see change occurring.

“Over time I can see the need for partnerships in the environment sector has increased massively and I feel like I can now detect there is much more openness within government to deliver projects with a partnership-based approach,” Dr Page said.

Right now, under Dr Page’s stewardship, South West NRM is partnering with DBCA on four separate projects, all with benefits for threatened species in the South West and with a combined investment in the partnership of just over $2 million. South West NRM has secured Natural Heritage Trust funding to support these projects as a member of the Australian Government’s national Panel of Regional Delivery Partners – a mechanism for delivering Federal funding for natural resource management and nature repair services where it’s needed most.

SAVING THE WHITE-BELLIED FROG

Among the projects South West NRM and DBCA are currently working on together are two designed to benefit the white-bellied frog.

One, funded via an Australian Government Saving Native Species grant, involves testing of a novel approach to rehydrate creek beds which have, at times, become too dry for the frogs to breed. An automatic irrigation system has been installed and activated. This consists of a 23,000L water tank, solar-powered pump, irrigation controller and an intricate maze of delicately installed reticulation pipe and sprinklers woven into the fragile ecosystem.

Data on soil moisture levels at the project site, measured by a series of sensors, are being transferred via satellite to the project team who are using specialist software to remotely and continuously track conditions. Soil conditions will be compared to an adjacent area where monitoring is also occurring but not being supplemented with reticulation. Then it’s more ‘frogging’ or monitoring of frog numbers to measure potential impact of the approach.

The second project, funded by the Australian Government Natural Heritage Trust, involves identifying new habitats for white-bellied frogs and testing suitability for potential translocation of new populations bred by Perth Zoo.

The two other projects benefit the hairy marron and western swamp tortoise, also funded by the Australian Government Natural Heritage Trust.

Only time will tell whether the various interventions can rescue these threatened species from the cliff edge of extinction. But what is clear is that their future plight would have already been written had it not been for determined species conservation experts coming together across the government and non-government divide, to carve out a way of working together effectively for the common good.

WHAT’S AN NRM?

South West NRM is one of 54 Natural Resource Management groups across Australia, and most have been in existence since the mid-90s. South West NRM began life as South West Catchments Council (SWCC) more than 20 years ago and right from the beginning, the organisation has worked alongside DBCA (and its predecessors), at varying degrees to help drive positive environmental outcomes in the region.

Dr Page believes it’s this passage of time that has allowed for South West NRM to mature as an organisation, enhancing the calibre of its governance as each year passed, while developing a track-record on impactful project delivery capable of nurturing DBCA trust. The result has been the laying of a strong foundation on which the two organisations are now capitalising for the benefit of nature in the South West.

Dr Page identified this achievement of mutual trust between organisations during her Churchill Fellowship as one of the keys to successful partnerships for environmental conservation.

WORKING TOGETHER

In a valuable position to cast an eye back over the full length and breadth of the South West NRM and DBCA relationship is DBCA’s Regional Leader Nature Conservation in the South West, Kim Williams.

He has worked for the department for more than 40 years and was even involved in helping shape the original organisational strategic direction of South West NRM in the 90s when it was first established – initially as SWCC.

Mr Williams has watched the relationship between the two organisations ebb and flow over two decades and says he’s certainly seen the relationship tested to the limits at various points throughout its development – largely in line with changing funding availability and shifting strategic objectives.

He feels it’s fair to say the environmental objectives at State and Federal level don’t always line up neatly which creates the need at times for intense negotiations, collaboration and problem solving between DBCA and South West NRM staff. But with a commitment from both parties to good, open lines of communication, a way forward has always been carved out as partners, ensuring positive, long-term environmental outcomes for the region are achieved.

“Over the years, we have certainly gained some considerable outcomes that wouldn’t have been achieved without NRM funding,” Mr Williams said.

On the current suite of projects, Mr Williams was positive about the cutting-edge nature of the various works which again he said could not have been undertaken without the funding that South West NRM had brought to the table.

SOUTH WEST NRM SPECIES FOCUS

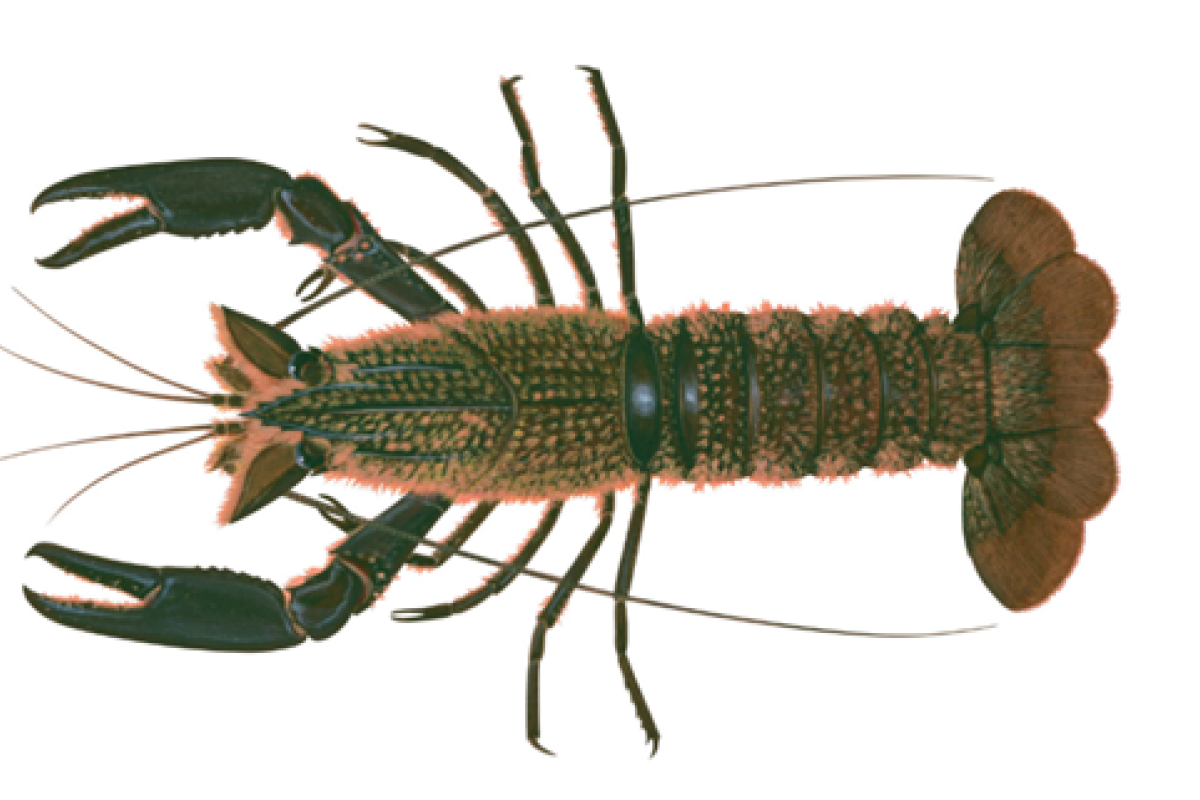

The hairy marron (Cherax tenuimanus) only occurs in fresh water in and near Margaret River.

It is similar in appearance and size to the more common and well-recognised smooth marron. It’s only distinguishable by a distinctive cover of short, bristled hairs on its head, down to its thorax.

The most significant threat to the species is hybridisation with smooth marron. It’s not always easy to tell a smooth marron and a hairy marron apart – particularly as the hairs are not obvious on juveniles. This makes the critically endangered hairy marron also vulnerable to fishing.

Hairy marron bred at Perth Zoo as part of the existing recovery program may be released in suitable locations to work towards establishing new wild populations.

Fauna surveys are being undertaken to search for populations of hairy marron in locations surrounding the existing known habitat, and protection measures are being implemented to prevent habitat degradation, grazing and interbreeding with smooth marron.

Research will also be conducted on appropriate methods for release of hairy marron to inform future conservation efforts.

Once feared extinct for over 100 years, the western swamp tortoise (Pseudemydura umbrina) is a critically endangered reptile species, now restricted to just two small remnant populations within nature reserves managed by DBCA. It has also been translocated to Moore River and Scott River.

The western swamp tortoise is small compared to similar species, with a short neck and shell length up to 15cm – weighing about 500g.

Funding has been made available to better understand the success of a translocation of the western swamp tortoise outside of its natural range to Scott National Park in southwest WA. The results will help inform a potential further translocation to this site. Traditional Owners will be engaged in monitoring the species.

The Margaret River burrowing crayfish (Engaewa pseudoreducta) is one five species of burrowing crayfish in WA that live in burrows rather than rivers, lakes or dams. They all have smaller tails than their freshwater equivalents and large claws for digging burrows up to four metres deep.

Though no bigger than your finger, burrowing crayfish contribute a great deal to life underground and are referred to as ‘ecosystem engineers’ because their burrows turn over and aerate the soil, providing air and nutrients to plant roots. The Margaret River burrowing crayfish is critically endangered and threatened by habitat loss through land clearing, farm dam construction, groundwater extraction and the drying climate.

Through fauna surveys and habitat protection measures, attempts will be made to identify at least 3 currently unknown populations of Margaret River burrowing crayfish.

An eDNA assay developed by DBCA under a previous partner project with South West NRM will be used to survey for their burrows in potential habitat on properties surrounding known populations of the species. Confirmed populations will be protected through fencing to exclude livestock and weed and feral animal control where needed.