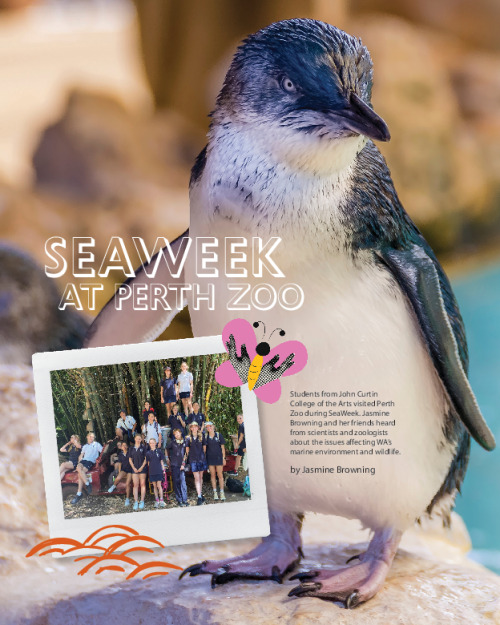

On 5 March 2025, I attended an event for SeaWeek at Perth Zoo with my school’s Roots and Shoots Club. Prior to the event, I hadn’t heard of SeaWeek, but I soon found out that it is a national campaign to bring awareness and education about marine environments to all Australians. The event brought both to my attention; I was more aware of the issues that face our seas and oceans, and I learned a lot more about the organisms that live in them.

The event was split into four parts, starting with an introductory talk by Dr Thomas Holmes, who is the leader of the Marine Science Program at the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation, and Attractions (DBCA).

In this talk, we learned that there are 24 marine parks, management areas, and nature reserves in Western Australia, making up about 50 per cent of our waters! There are different levels of restrictions in these marine parks, each helping to protect these ecosystems and allow different types of use for people.

The next activity was a panel with Research Scientist Dr Molly Moustaka and Technical Officer Daisy Church, who both work at DBCA. It was a very relaxed and open atmosphere, and many questions were asked about what marine biologists and researchers do for work, their field experiences, and the pathways you can take to enter these careers.

Turning up the heat

DBCA Science Communication and Education Officer Clodagh Guildea presented the next workshop, which was about flatback turtles, a species that is endemic to Australia. We walked to the crocodile enclosure where we learned that all reptiles, including turtles, are ectotherms, and use heat in the environment to regulate their body temperature.

Through an interactive activity, we explored how the temperature of the sand in a turtle nest influences the sex of the turtle hatchlings when they are incubating in the egg.

A few of us received printed out pie graphs expressing the ratio of males to female in a clutch of eggs at different sand temperatures, which we placed on a graph on the floor.

It really helped us visualise the relationship, and we could see how sensitive the hatchlings are to small temperature changes (see ‘The heat is on: flatbacks and a changing climate’ LANDSCOPE winter 2021). Across WA’s Pilbara beaches, the average sand temperature is 30ºC, and these beaches produce around half male and half female hatchlings. However, an increase of just one degree could mean mostly females are produced, and if nest temperatures become higher than 32ºC, the hatchlings will experience heat stress and could die.

We discussed ways to manage the impacts of increasing temperatures on turtles. Suggestions included sprinkling water on the sand and installing shade- sails on beaches.

A more labour-intensive option is to translocate the eggs and incubate them at controlled temperatures, so the ratio between male and female hatchlings would be sustainable. Some of these solutions might be needed at Pilbara beaches, where 30 per cent are at high risk of being too hot by the end of this century.

I wasn’t aware of how turtles are impacted by climate change in WA before this workshop, and it was very compelling to learn about and discuss these issues.

Penguin peril

The final workshop by Research Scientist Kevin Crook covered little penguins (Eudyptula minor), which reside around southern Australia and New Zealand. WA has the most northern, and therefore hottest, penguin colonies, making them vulnerable to climate change.

We learned that one of these colonies is on Penguin Island, less than 700 metres off the coast and halfway between Perth and Mandurah. It has been well studied

since the 1980s, but since 2008 the penguin population has experienced a sharp decline, with an estimate of only 114 penguins in 2023. This could be due to several reasons, but we explored the lack of food as a key cause.

When raising chicks, adult penguins travel around 30 kilometres away from home each day to hunt for food, bringing it back at night to feed to their chicks.

However, if they don’t collect enough food for both themselves and their chicks, they will prioritise themselves.

This can lead to a smaller population of chicks because although the breeding success of penguins is consistent through the years, if there is less food available, more chicks will perish.

We explored this scenario through an activity; we were each a ‘penguin parent’ with a chick, and ‘fish’ were scattered across the lawn. We were given a dedicated amount of time to forage enough fish for ourselves and our chick, but we would have to prioritise ourselves if we didn’t collect enough.

After each round, the sea temperature increased, and fewer fish were available in the environment. It was fun and sobering at the same time, and an effective way to experience how challenging it is for real penguins to live with the impacts of climate change.

I was recently able to watch penguins come onshore to their chicks in Tasmania, so it was especially engaging for me to be able to link that experience with all the knowledge I learned in this workshop.

An unforgettable experience

I learned a lot during SeaWeek at Perth Zoo. It was very captivating to hear from professionals about their field of work, and eye-opening to learn about the issues affecting our marine ecosystems right here in WA.

It was amazing to be able to walk around the zoo and observe the animals we were learning about, especially the little penguins. I gained a lot of awareness about the roles of DBCA, marine parks, and the impacts of climate change on our marine life, and I looked forward to coming back next year if I am given the chance!