Photo of area affected by Phytophthora Dieback

What is Phytophthora Dieback?

Phytophthora Dieback (dieback) is a plant disease of native ecosystems.

What causes dieback?

Dieback is caused by a plant pathogen from the genus Phytophthora. Over 60 species of Phytophthora have been detected in Western Australia, with almost 40 of them detected in native ecosystems and the others in agriculture and horticulture. There is significant overlap between species detected in horticulture and native ecosystems.

Is Phytophthora native to WA?

Some of the Phytophthora species that occur in WA are believed to be native. However, Phytophthora cinnamomi, the species with the greatest impact on biodiversity, is not native. It is thought that P. cinnamomi originated in South East Asia and was introduced to WA with infected horticultural plants in the early 1900s.

Which plant species are susceptible to Phytophthora?

In WA's south-west bioregion, more than 40 per cent of native plant species are considered susceptible to the disease including many from the Proteaceae (banksia's and hakeas), Ericaceae (snottygobble), Myrtaceae (eucalypts) and Xanthorrhoeaceae (grass-trees) families. Threatened flora are at even greater risk with around 56 per cent being considered susceptible (Shearer et al, 2004).

Outside of our native flora, many of our garden, ornamental and horticultural species are also susceptible to P. cinnamomi.

See the Indicator Plant lists for each of the major WA regions in the Downloads section below.

How does Phytophthora spread?

- Phytophthora spreads naturally by moving through soil and the roots it infects, and in run-off.

- Animals spread Phytophthora when infested soil gets caught in their feet and fur and it drops off in uninfested areas.

- Humans spread Phytophthora when they disturb and move infested soil. Through their activities, humans have spread Phytophthora further and faster than any other means of spread.

How does Phytophthora kill plants?

Under optimal conditions (moist and warm) Phytophthora produces zoospores in large numbers. Zoospores swim toward plant roots, as they are attracted to the chemicals that the roots release. Zoospores adhere to and infect the roots producing mycelium. The Phytophthora mycelium draws nutrients from plant cells fuelling further growth and reproduction of the pathogen but killing the plant cells in the process. The entire plant dies if the root system becomes extensively infected or if Phytophthora reaches the collar (stem/trunk base) of the plant, cutting off water and nutrients to the crown (leaves and branches).

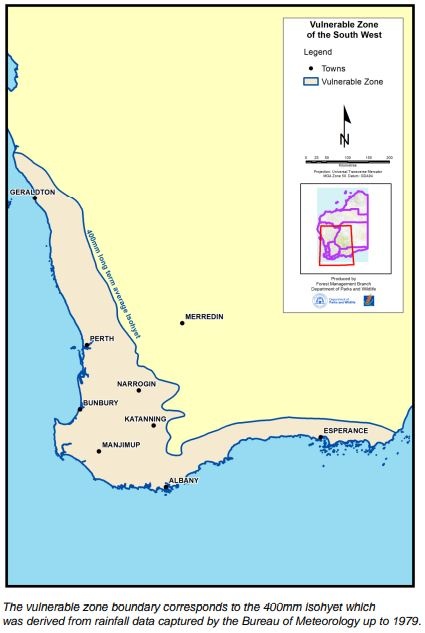

Where dieback occurs in WA

Dieback occurs in the south-west of WA in an area called the vulnerable zone. The conditions here allow Phytophthora to persist, establish and cause dieback in natural ecosystems. Not all parts of the zone are equally vulnerable, dieback is particularly widespread in the areas of 800 mm+ annual rainfall, i.e. forested regions, the Stirling Range.

The impacts of dieback

The impacts of dieback are negative, permanent and irreversible. Dieback affects the environment as well as social, cultural and economic values.

The environmental impacts include reduced biodiversity, reduced biomass and reduced food/shelter for native animals as well as increased weed invasion and increased areas of bare soil.

Our social and cultural values are also impacted with the disease causing the loss of natural heritage values, culturally significant species, and cultural and heritage sites. Economically, the disease increases our management costs and has a significant impact on tourism when natural attractions are degraded.

To find out more about the tools, programs and resources used by the department visit the How the department manages dieback page.