Wadandi people, the Traditional Owners of the area around Geographe Bay and the Capes in Western Australia’s south-west, have many stories of whale strandings on their Country throughout history. When mammang (Wadandi language name for all whale species) beach themselves, it can mean culturally that ancestors are coming home.

Traditionally, as the carcasses decomposed, and their oil entered the water, large fish and sharks would come into the shallows providing hunting opportunities. A large ceremony would be held, and the people would gather to cook, share food and celebrate.

For people from many other cultural backgrounds, the initial instinct when confronted with a mass whale stranding is to want to help return the whales back to the deeper water where they belong.

Recently, scientists have become aware that this approach isn’t optimal for the wellbeing of the whales. After becoming stranded in shallow waters or lying on the sand for extended periods, they may experience significant injuries and extreme stress.

Ultimately, during these events many animals are not able to be returned to sea, and either perish during mass strandings or are euthanised in the interests of animal welfare.

On 25 April 2024, a mass stranding of long-finned pilot whales at Toby Inlet near Dunsborough resulted in 31 known whale deaths. Less than 12 months earlier, in July 2023, 97 pilot whales had died in a similar mass stranding event at Cheynes Beach near Albany.

These occurrences offered scientists valuable opportunities to gather data and develop new insights.

From a scientific perspective there are many hypotheses as to why mass whale strandings occur including illness, geographic hotspots due to the shallow bathymetry, navigational errors, and interference from human-made noise.

While the uncertainty and complexity can be challenging for people to accept, it is unlikely a single cause applies to all strandings. Instead, each stranding event needs to be considered individually.

WHAT WE KNOW

Species that are more likely to mass strand such as the long-finned pilot whale (Globicephala melas) are pelagic, which means they live in deep, offshore waters a long way from land. They are not frequently encountered in coastal waters and strandings can be an opportunity to learn more about them.

An interesting feature of the species is that they live in large, very tightly knit groups at sea.

Scientists know from studies of wild, free-ranging pilot whales that they live in matrilineal pods, led by female matriarchs. The offspring, including males, remain in their natal pods for life, which is peculiar to a few whale species (killer whales, false killer whales, pilot whales and sperm whales).

Inbreeding is prevented, as breeding opportunities are available when unrelated pods interact with one another. This complex social structure and way of life has been revealed through the study of their behaviour in the wild and confirmed through research on their genetic makeup from wild pilot whales and groups that have stranded.

LOOKING FOR RELATIONSHIPS

To contribute to this body of knowledge and improve our understanding of the pilot whales that use Western Australian waters, biologists and geneticists at the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA) have collected small tissue samples from the deceased individuals at recent strandings. They hope to confirm the relatedness between individuals within the pods that stranded at Cheynes Beach and Toby Inlet.

In a collaboration with Flinders University, DBCA scientists are also investigating how related the pods are across Australia using data collected at strandings as far away as Tasmania.

Once the data has been fully analysed, scientists will be able to determine whether genes are shared between pods or are unique, and this will also help inform the population and conservation status of pilot whales in Western Australia.

For example, currently it is unknown if there is one large population of pilot whales that moves around the south and south-west coast of Australia, or smaller populations that do not mix or breed together.

Comparisons that have been made between New Zealand and Tasmania have shown big differences between whale populations in these two places, so it will be interesting to see what is found at a local level and within Australia.

POPULATION INFORMATION LACKING

The conservation status of pilot whales globally is ‘least concern’ based on population estimates from the northern hemisphere that suggest a healthy population of hundreds of thousands.

Such estimates are unavailable for the southern hemisphere aside from an estimate from the 1970s in Antarctica of several hundred thousand.

These dated data and ongoing data deficiency precludes scientists from knowing the actual population size for Australia and being able to explore trends in the population to know whether it is stable or not.

The population size and status are key pieces of the puzzle that scientists and conservation managers would like to know to better understand how these mass strandings impact the overall population.

KNOWN VULNERABILITIES

Other important questions that inform conservation status and impacts on these species include better understanding diseases and vulnerability of local populations.

Diseases such as cetacean morbillivirus can occur in pilot whale populations and some outbreaks can result in multiple mortalities.

Understanding when outbreaks occur can have population level impacts for the species, noting that cetacean morbillivirus is not contagious to humans.

However, other infectious diseases are transmissible to humans.

The latest emerging health concern for wildlife and for people is highly pathogenic avian influenza. This disease has jumped between species, with thousands of sea lions dying in South America and recent detections in Antarctica in seabirds. To date, Australia is the only continent that has not been impacted.

CAN SCIENCE SOLVE THE MYSTERY?

One of the key roles of scientists attending strandings is to collect samples to test for a range of diseases. This work is done through collaboration between state government agencies and aims to identify or exclude those diseases that pose a risk to people.

Testing conducted on the pilot whales from the Cheynes Beach stranding has led to some interesting findings, such as a bacterium detected in several whales that has puzzled pathologists and has been added to the suite for testing at future strandings.

The challenge is to confirm whether this bacterium, known to cause disease, contributed to the cause of the stranding or was an incidental finding.

Another important question to ask is whether any contributing human factors can be identified.

Noise is known to disrupt the behaviour of whales and dolphins and some intense noises can damage the ears, causing hearing loss if they are exposed at close range. But how do we know if noise has contributed to these strandings? Although a shared concern nationally and globally, few scientists have tackled this question.

Researchers took on this challenge by using a medical approach and specially designed equipment used to scan human heads and create detailed images so that they could take a closer look at the ear parts of three pilot whales from the Cheynes Beach stranding.

The researchers had not anticipated how much of a logistical challenge this would be. It required the removal of heads from the deceased whales and their transportation to Perth to a medical imaging facility at CSIRO. It took three people and a lot of lifting and manipulation to manage this unusual delivery and store the heads in deep freeze until they could be scanned.

The CT scanner is designed for humans and the sheer size of the whales’ heads meant only the youngest whale’s head would fit inside the bore of the machine for imaging.

Analysis of the younger whale’s head found no evidence of catastrophic trauma such as holes in the middle/inner ears, but more detailed investigation is required to rule out more subtle perforations.

The heads of the other, older two whales will now undergo a different process of micro-CT scan and a detailed dissection. For future events, we will now also have the option to use a higher resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for investigation of potential acoustic damage, due to the generous offer from a local veterinary clinic to use their facilities after hours. The cost of the scans and testing can make this work costprohibitive among competing research priorities.

INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATION

Scientists from Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and Iceland have formed a group, bridging the distance across oceans, to share information about pilot whale mass strandings, which occur worldwide.

The focus of this group is to better understand what occurs leading up to the strandings by compiling and reviewing video of pilot whales to characterise their pre-stranding behaviour and group cohesion.

Sometimes, whales strand unobserved, and it is not until they are ashore that they are reported, so important insights into the events preceding the stranding are missed. Armed with this early insight, it is hoped the information not only improves preparedness for strandings, but also informs animal welfare considerations and the decision making around euthanasia.

LOOKING FORWARD

Once the pre-stranding behaviour is better documented and understood, this group of hopeful scientists want to also investigate the behaviour during and after the stranding. When pilot whales are refloated and released there’s an opportunity to see if there are things that can be learned, which will lead to better outcomes in future events.

Mass strandings are a global phenomenon that have occurred for thousands of years and will continue. These events offer valuable learning opportunities.

The Wadandi people hope that these events may also be embraced as an opportunity “for community to gather on the beach to celebrate their lives” [Wadandi Traditional Owner Toni Webb] and that cultural ceremony might become part of whale stranding response and protocols in the future.

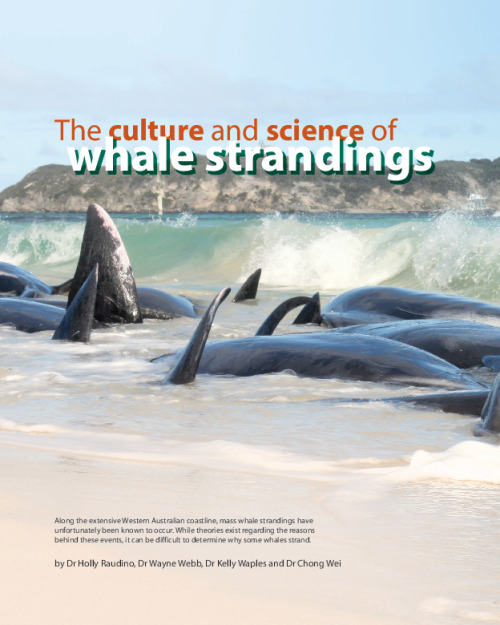

Mass whale strandings unfortunately occur along Western Australia’s coastline. While theories exist regarding the reasons behind these events, scientists remain uncertain about why some whale species are more prone to mass stranding.