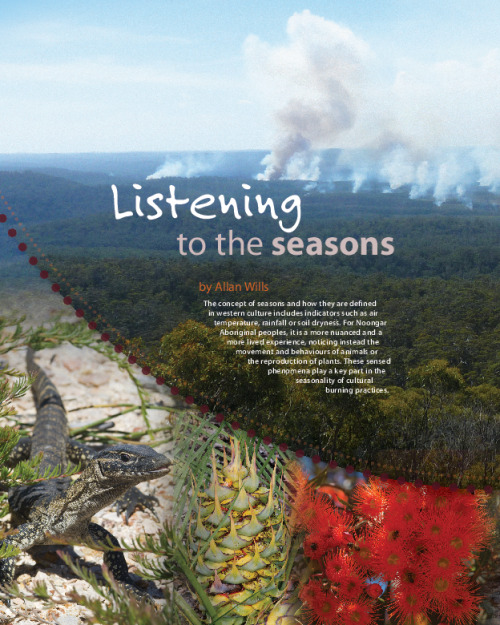

Several concepts of season have been used or proposed in south-western Australia, and these connect

differently to fire seasonality, cultural history, biological features and climate patterns.

European colonisers of Australia brought with them the concept of four seasons linked to the Gregorian calendar. These seasons continue to be a broad descriptive framework used by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology, with spring falling in September to November; summer in December to February; autumn in March to May; winter in June to August.

In south-western Australia the Noongar Aboriginal peoples retain a complex concept of seasons with a six-season calendar recognising climate, resources, and biological phenomena as seasonal cues.

The concept of boodjar

Central to the Noongar six season calendar is a representation of boodjar; a concept that does not translate easily to English as it is an encompassing concept of location as a lived experience including landscape and place as astronomical, climatic, biological, and geographical phenomenon and custodianship through cultural beliefs, lore and knowledge.

It can be interpreted that, above all, boodjar is the phenomena of place as a lived experience relayed in stories, songs and dance that connect across time.

Conceptually, the seasons are experienced cyclically as part of boodjar in a multitude of sensations.

“The six seasons are made palpable through the presencing of different natural things… registered by sight, touch, taste, smell, and sound,” John Charles Ryan wrote in his paper Toward a phen(omen)ology of the seasons: The emergence of the Indigenous Weather Knowledge Project in 2013.

Seasonality and fire

Burning regimes across millennia have been determined by the cultural practices of the first human inhabitants of south- western Australia, and the frequency of lightning ignitions.

The use of fire by Noongar peoples was highly seasonal according to records from pre- and early colonial times.

However, there are limitations to pre-colonial and early colonial accounts such as very little detail on the cultural subtleties of Aboriginal burning.

Early colonists recorded that Noongar peoples carried firebrands in all seasons and so are likely to have set fires in all seasons. Another possible limitation of pre- and early colonial observations is that fires of different purposes had different visibility, as well as the differences in visibility of fires across the seasons.

Use of fire was likely to be partitioned according to gender, leading to differences in locations burned and types of fire techniques. Fires observed in pre-colonial and early colonial records are known from the Noongar season djilba (equivalent to August and September, or early to mid- spring in the southern hemisphere) and greatest during the season birak (equivalent to December and January, or mid to late summer in the southern hemisphere).

However, consideration of only the timing of fire misses cultural considerations of both the purpose and location of fires in the landscape, and the motivations for the timing of fire.

The flammability paradox

If the Noongar peoples burned the land at times when conditions were hot and dry, and the landscape was most flammable, why was the result not large, uncontrollable fires?

We can hypothesise that the answer lies in fuel availability and discontinuity— burning of relatively young and light fuels to larger mosaic of fuel ages, and the locations that were burned at particular times.

It is understood that Noongar peoples moved about the landscape according to the availability of food and water, and for cultural considerations. Particular parts of the landscape would have been burned for purposes such as flushing vertebrate game by men, or promoting productivity of vegetation, food and materials by both men and women.

The mosaic could have been created by a combination of fires from burning practises of Noongar peoples and by inevitable lightning ignitions. Indeed, that such a mosaic is possible has been demonstrated in modern times by Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions fire managers using aerial ignition to introduce fire into London forest block near Walpole at intervals of one to three years between 2002 and 2011. The outcome was a fine grain mosaic of discontinuous patches of different fuel ages with different abilities to carry fire.

Water, food and certainty

It is believed that Noongar seasons are cued by adaptive responses and, in turn, cue human adaptive responses. Knowledge of what the animals, plants and spirits are doing within the Noongar seasons, and their place within boodjar, allows an understanding of conditions for, and outcomes of, cultural burning. The scale of cultural burning is much finer compared with the variability of modern burning.

Different phenomena are timed according to ecological relationships with several factors, including but not limited to the availability of water.

The cycle of water availability through the landscape has consequences for landscape flammability, the timing of recurring biological events like flowering plants and animal reproduction, and human behaviour, and the Noongar calendar is dynamic and responsive to that cycle.

The areas of landscape available to Noongar peoples varied seasonally with the presence drinking water, as well as water available to culturally important plant species, and Noongar peoples moved through the landscape accordingly.

Thus, Noongar burning of the landscape hinged on the moisture cycle in (at least) three ways—its effect on where people were in the landscape, why they were there, and which parts of the landscape were deliberately burnt; its effect on fuel flammability and fire characteristics; and its effect on plants and animals as they affected food and resources.

Noongar peoples understood the complex relationships between fire, water, and biological productivity— as is implicit in the six season Noongar calendar.