For as long as I can remember I have been fascinated by the natural world around me. So, interpreting nature and landscape through photography just seems to come naturally. I’m not a gear junkie; I just see cameras as tools to capture what I’m seeing and feeling about what is in front of me.

My sister gave me my first camera when I was nine, an Agfa box brownie equivalent. We lived on an orchard in Parkerville in the Perth Hills on the edge of John Forrest National Park, surrounded by jarrah bush and granite outcrops. I’d walk to school through the bush.

In the early 1960s, a young schoolteacher and his family bought the house in the bush block over the road— Eric McCrum OAM, was ABC radio’s ‘bird man’, known for his incredible knowledge of birds and his ability to accurately vocalise bird sounds.

I would spend hours in the bush with Eric, absorbing his bushcraft, wildlife observation, and the science of photography with his ground-breaking 35-millimetre Praktica; one of the very first single lens reflex (SLR) cameras.

I was hooked. When I was 14, I worked over Christmas school holidays in Albert’s Bookshop in Perth to earn money to buy my own SLR. Thus began a life of exploring my relationship with nature and interpreting it through a lens.

In another amazing photographic coincidence, my girlfriend’s family were great friends with Richard Woldendorp who became arguably Australia’s greatest visual interpreter of the Australian landscape. Richard and I became lifelong friends, and I absorbed the art of landscape photography from him.

Blossoming career

I left home aged 17 and took a ‘gap decade’, travelling north to Derby, and then on to Broome to work in the cattle industry. When I returned home during the wet season, my storytelling ‘slide show’ photography blossomed, showing the largely then-unseen Kimberley landscape, people and cultures.

I entered competitions and won prizes for my photos. However, I never pursued photography as a career, rather as a means of telling stories. I then studied Applied Science-Biology.

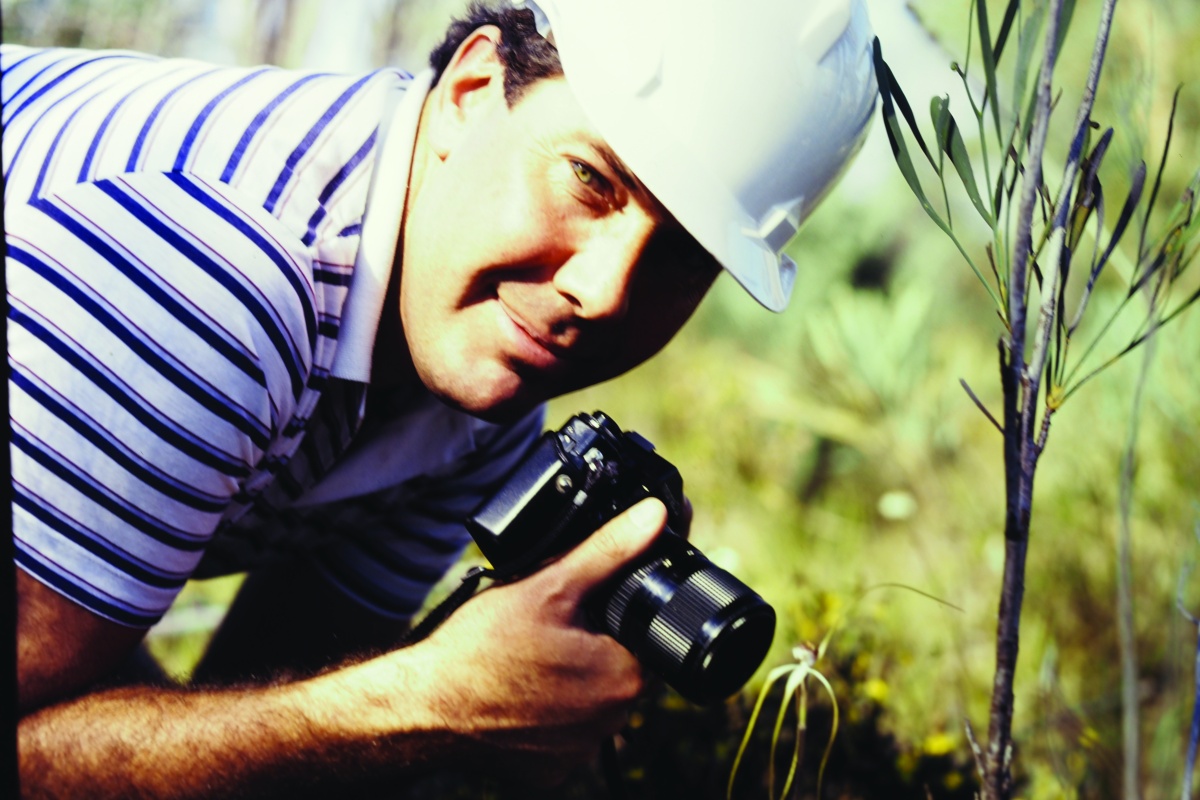

My studies led me to get a job with the Western Australian Forests Department as a seed collector. I travelled all over the State collecting native plant seed for nurseries. Of course, I took my camera and told more WA landscape stories through slide shows.

Eventually this caught the eye of the department’s Forest Focus magazine editor, and I was invited to contribute on a regular basis. This took me out of the seed store into a role in community liaison.

When the DBCA predecessor, Department of Conservation and Land Management (CALM) was formed, amalgamating (somewhat controversially initially) the Forests Department, the Wildlife arm of Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, and the National Parks Authority, I was on the first editorial committee of the proposed new corporate magazine. I was even involved in the debate about the name—LANDSCOPE. Thus, I became a foundation contributor to the magazine including its first few cover photos and photo essays.

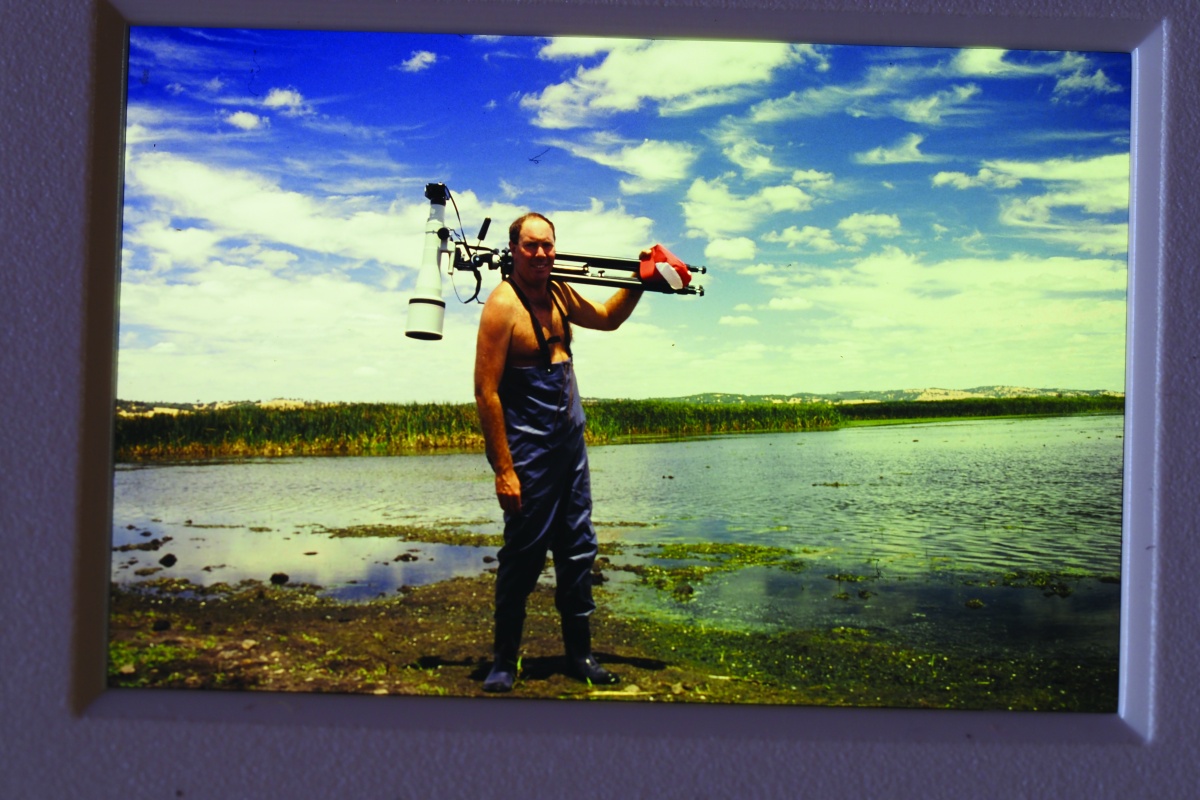

My assigned mission was to “bring them together”. What a mission! What a privilege! I was given license to travel the State to gather stories and images about management of national parks, forests and nature conservation research. I got to go on expeditions with the locals all over the State (see ‘Lasting adventures’ LANDSCOPE winter 2025). I got to see a problem crocodile moved in the lower Ord and the first national park signs put up in Purnululu.

I became interested in writing and started studying it at university. My career morphed into interpretative signage— combining writing and photography— mostly visitor introductions to recreation sites, complemented by factual, stimulating explanatory information.

That shift took me to karri country as Regional Leader of Visitor Services in Manjimup for 15 years, and finally for three years in the Pilbara Region in national park management.

A different light

I retired from the department in 2009 to return to our farm at Smith Brook amongst the karri forest. I continue to visit national parks and nature reserves in remote places all over the State and so remain an invited contributor to LANDSCOPE.

I confess I was a little tardy moving from film to digital and I’m a bit of a purist. I still don’t do creative editing apart from minor colour correction. New cameras are smarter, lighter, comparatively cheaper, and the image quality is sensational. I get most satisfaction these days from producing abstract images of nature and landscape, especially aerials of deserts and coasts.

I meet new people in wild places and introduce myself and get “I know your name—where would that be from?” and often it’s traced back to LANDSCOPE. It gives me a great sense of satisfaction and pride that through the images I’ve created of the environment in Western Australia and its conservation over the forty years, my own legacy is worthy.

These days I look forward to receiving the texts and image requests for the next edition of LANDSCOPE. I see it as a challenge to interpret what the author is saying so that readers get it too.