From traversing the rugged landscape of the Kimberley, to uncovering rare flora and fauna in the south-west; LANDSCOPE Expeditions promised a share of adventure, discovery and camaraderie.

Starting in 1992 with a trip to the Gibson Desert, the idea for the expeditions was inspired by The University of Western Australia’s Extension program led by Jean Paton (nee Collins) and Western Australian Naturalists’ Club excursions, led by Kevin Coate and Kevin Kenneally, both of which conducted scientific research trips throughout Western Australia. As the program was designed to raise public awareness of plant and animal species, the eligibility requirements for the volunteers joining the expeditions were simple.

“The only qualifications needed are general good health, common sense, enthusiasm, an ability to adapt to other people, and a sense of humour,” former LANDSCOPE managing editor, Ron Kawalilak said at the time.

Participants were members of the community, young and old, who would join expedition teams that consisted of departmental scientists and regional staff. On each trip, the expedition leaders were responsible for keeping an expedition diary and thoroughly documenting details— from scientific discoveries to personal anecdotes and humourous moments.

Flicking through these honest, authentic diary entries in modern times provides an insightful glimpse into the past. While useful to understand scientific discoveries, these diary entries have also captured the spirit of the expeditioners through the selection of memories, giving a relatable human element to the formulaic structure of science.

Averaging between five and ten expeditions per year, the location of the trips depended on scientific research priorities and public appeal. A full list of all the trips for the year ahead was detailed in an Expeditions Program, giving potential volunteers a snippet into each of the locations, the field work to be conducted and the cost and duration of the trip. A brief biography of the head scientists and expeditioners leaders was also included, giving expeditioners a chance to get to know the leadership.

Paving the way

While the LANDSCOPE Expeditions program has concluded, the legacy of research and scientific contribution expeditioners made continues to hold value. Several of these trips paved the way for established and continuing Parks and Wildlife initiatives, such as the conservation program Western Shield, which works to reduce introduced predators and protect local fauna (see ‘Restoring the balance: 25 years of wildlife protection’, LANDSCOPE, Spring 2021).

Laying the foundation for this program was the introduction of Project Eden in the 1990s. Project Eden is an initiative that aimed to reintroduce native species and remove all foxes and feral cats from part of the Shark Bay World Heritage Area.

An expedition in 1998 saw participants recording data on both reintroduced species and the feral cat population. Project Eden is still going today, having inspired the Dirk Hartog Return to 1616 restoration project.

Citizen scientists are often limited by their resources and capabilities, which made these expeditions appealing to those who wanted to make a difference, but did not know where to start. The major attraction to volunteers was the diverse learning experience the expeditions offered, alongside knowledgeable scientists in the field. Many volunteers became repeat expeditioners, allowing them to hone their skills each time round.

Hands on experience

Volunteers for the expeditions ranged from 13 to 81 years, and by the turn of the millennium in 2000, more than half of the volunteers had been repeat expeditioners. One woman even signed up for her seventh expedition at the age of 79.

There was the sense of adding a small piece to the conservation puzzle, with volunteers knowing the work they were doing would benefit the environment for generations to come.

Often, biological surveys were carried out in remote areas where minimal work had previously been conducted.

This meant each survey provided a standard for which future observations could be compared. Biological surveys typically involve the recording of animal populations, flower patterns and other notable natural processes in the area.

Kevin Kenneally was the Scientific Coordinator of LANDSCOPE Expeditions and went on many of the trips himself.

Discovering new things was always a highlight of a trip.

“So many new discoveries were added to science, it was one bit of excitement after another,” Kevin said.

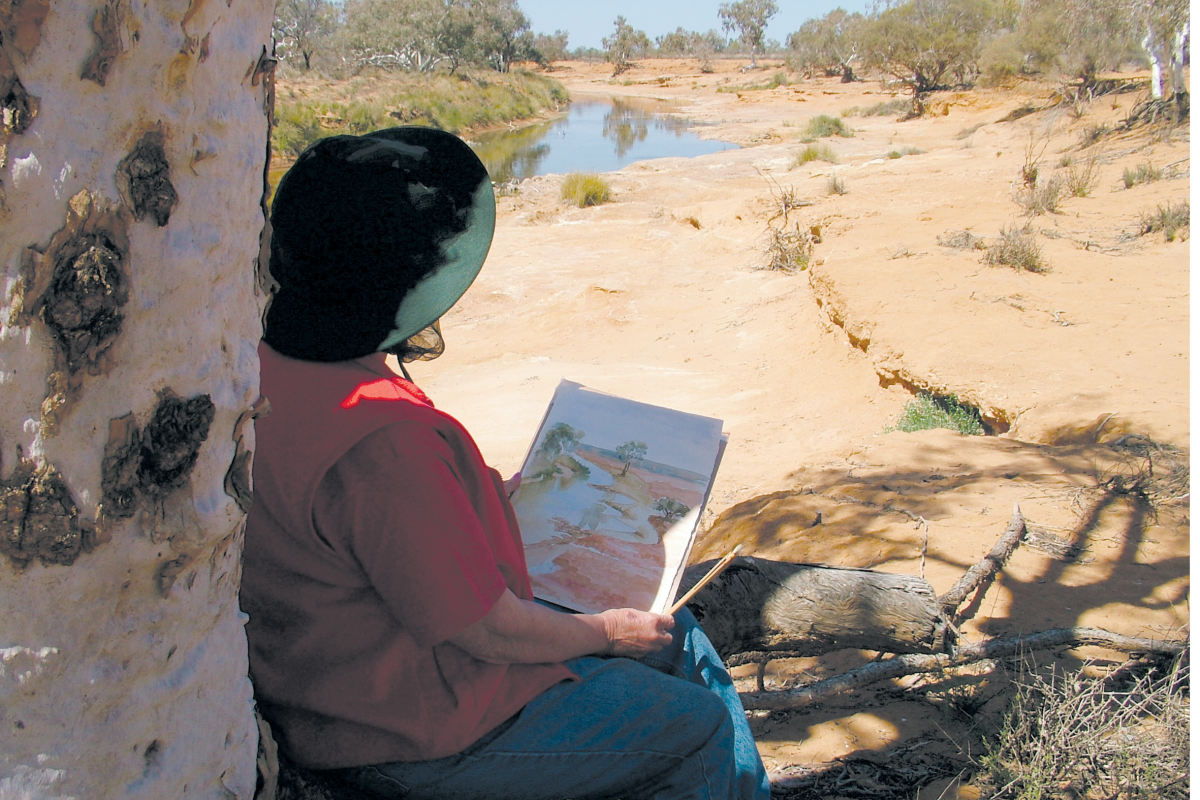

With many volunteers coming from city backgrounds, the trips also provided an escape to nature, away from the bustle and business of everyday life. While the expeditions were scheduled and involved manual work, they were also a way to connect back to the natural world.

Hearing animal cries while at a remote camp or listening to birds at dawn and dusk allowed participants to feel far away from the urban demands of the city.

With tourism perpetually evolving, these expeditions also appealed to an audience interested in nature-based tourism experiences. They were an opportunity to explore some of the unique treasures found in WA, combined with an element of scientific philanthropy. There were instances of volunteers and scientists coming from overseas to be involved, many returning for multiple expeditions.

To add to the tourism marketing of the expeditions, all volunteers were given a LANDSCOPE Expeditions duffle bag, thermal mug, stubby holder, lanyard and name badge. This merchandise standardised the luggage brought by each of the members while also serving as a valuable marketing opportunity.

However, perhaps the best marketing opportunity for the trips was not the merchandise, but rather the reputation for excellence the expeditions established.

Volunteers went away from the trip full of freshly acquired knowledge and experiences, which they discussed with friends and family alike. Rather than a marketing program, the expeditions relied on news coverage garnered from the occasional journalist invited on an expedition. Word of mouth was often the best way to attract the attention of prospective volunteers.

Contributing to this reputation for excellence was the unblemished safety record of the expeditions. Throughout its entirety, there were no significant incidents or medical emergencies. Kevin Kenneally attributed this pristine track record to thorough training and planning by expedition organisers and project leaders, such as alerting the Royal Flying Doctor Service of the expedition’s route and the number of people involved.

While the expeditions were pitched at a cost that allowed the department to break even, any left-over funds went directly to a trust fund. This could only be used towards future research and conservation projects. By the year 2000, expeditioners had contributed three-quarters of a million dollars towards Western Australian wildlife and conservation research, which only grew throughout the remaining years.

Leaving behind a lasting impression of discovery, determination and scientific discipline, the LANDSCOPE expeditions embodied the true potential that comes from a collaboration of scientists and everyday people wanting to give back to nature.