Millstream Chichester National Park forms part of the Yindjibarndi and Ngarluma peoples’ traditional lands and was an active pastoral station for more than 100 years.

The park was previously two separate national parks; Millstream and Chichester, which joined as one park in 1982. It is now recognised as a national park with significant natural, recreational and cultural values.

The arid-land plants and animals respond to infrequent rainfall events while the wetlands support diverse plant, bird and invertebrate species. Many of these are endemic and rely on the permanent water source at Millstream.

The water that feeds the Millstream oasis springs from an aquifer, or natural underground reserve, contained in the porous dolomite rock. This aquifer is fed by the Fortescue River (Yarnda Nyirranha) catchment, which includes run-off from the Hamersley Range.

The Millstream area is a Priority 1 catchment and, used in tandem with the Harding Dam, the aquifer supplies water to industry and for domestic use to the residents of Wickham, Roebourne, Point Samson, Dampier and Karratha.

Cultural values

The Millstream Chichester area is a very significant cultural site in northern Western Australia. Cultural and mythological importance stems from thousands of years of occupation, with Millstream being the home of the mythological serpent or warlu, whose presence is still strongly felt at Nhanggangunha (Deep Reach Pool).

All the pools are significant in this regard and warrant a high level of respect. The broad area of land straddling Yarnda Nyirranha from the Hamersley Range through to the Chichester escarpment is the homeland of the Yindjibarndi people.

Ngarluma people’s lands run from the Chichester escarpment northward to the sea. Aside from its highly important spiritual significance, Millstream was an important campsite for inter-tribal meetings. Yarnda Nyirranha provided food and water, particularly during drier months.

Along the river, Indigenous people had a varied diet of mammals, fish, reptiles, grubs, eggs, honey fruits and root vegetables. Extensive areas were burnt to create natural paddocks and attract kangaroos. The dry climate meant that knowledge of the locations of waterholes was important. The Ngardangarli people were skilled in land management and were nomadic within their traditional boundaries.

Yindjibarndi people continue to come to the park to spend time on Country and to carry out customary activities. They meet with the Pilbara Parks and Wildlife Service at the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA) to guide the strategic direction of the park.

The environment

The Chichester Range rises sharply from the coastal plain and includes rocky peaks, tranquil gorges and hidden rock pools. Snappy gum (Eucalyptus leucophloia) woodland and hard spinifex (Triodia wiseana) clumps cover the stony plateau, which gradually slopes down to the bed of Yarnda Nyirranha before rising again to the vast bulk of the Hamersley Range. Along the river lies the Millstream oasis with its string of deep spring-fed pools fringed by sedges, palm groves and silver cadjeput (Melaleuca argentea) forest—some of the largest of its type in the Pilbara.

Wildfires caused by lightning strikes can occur frequently during summer. An extensive prescribed burning program with Yindjibarndi Elders and rangers is carried out annually for biodiversity and asset protection. Burnt areas recover quickly after rain and provide a variety of resources and habitats for local wildlife.

Wildlife is abundant in areas of the park close to water. Rock holes, riparian zones and river pools support a thriving ecosystem. On the plains, many species of animal adapted to aridity can be frequently seen, and the transition zone between moist and dry environments is particularly diverse.

Plants flower year-round following rain, but most spectacularly in winter (June to August) when blankets of tall mulla mulla (Ptilotus exaltatus) and Sturt’s desert pea (Swainsona formosa) cover the landscape. The solid yellow flowers of wattles and sennas provide a dramatic contrast to the hard red earth and chocolate brown rocks. Plants more typical of the tropical north grow near permanent water pools; here forests of silver cadjeput and Millstream fan-palms (Livistona alfredii) can be seen.

The Millstream palm, with its fanned, grey-green leaves and smooth bark, is relict from the deep past when rainforest covered the Pilbara in past times with much higher rainfall. Twenty-two species of dragonfly and damselfly have been recorded in the Millstream wetlands, and over 500 species of moths.

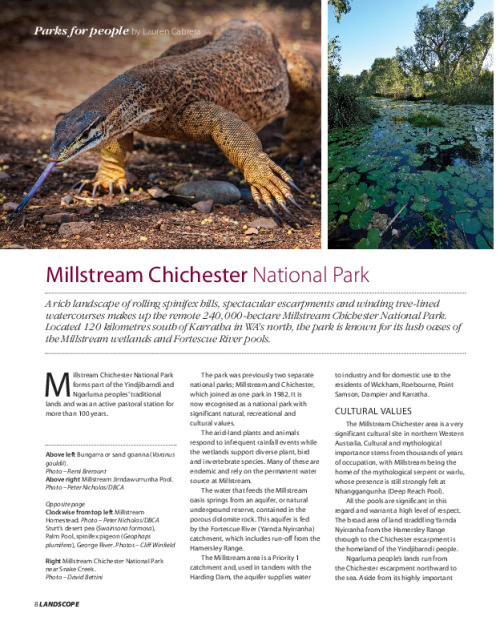

Almost 100 reptile species and nearly 150 bird species call the park home. Resident mammals include the endangered northern quoll (Dasyurus hallucatus), little red antechinus or kaluta (Dasykaluta rosamondae) and the euro (Osphranter robustus). Many of the bird species are delightfully coloured and can be seen during the cooler hours of the day, especially near water, and reptiles are prolific. Lizards are seen frequently on rocks and trees; even large species such as the Pilbara olive python (Liasis olivaceus barroni) and bungarra or sand goanna (Varanus gouldii) make an appearance.

Introduced species such as date palms and cotton palms were once prolific at Millstream. They competed with native vegetation, blocked creek channels and encouraged wildfires. The majority have been removed and the area rehabilitated. Other weeds at Millstream include the Indian water fern (Ceratopteris thalictroides), hairy water lily (Nymphaea pubescens) and stinking passion flower (Passiflora foetida).