Chuditch

Western Shield is WA’s largest conservation program working to manage introduced predators for native species conservation.

Protecting WA’s vulnerable native animals

Western Shield aims to protect native species, primarily small and medium-sized mammals and some ground-nesting birds and reptiles, that are vulnerable to predation by foxes and feral cats.

Foxes and feral cats have been identified as a key cause of the extinction and decline of dozens of native animal species across Australia. Suppression of fox and feral cat numbers is a crucial step in successfully reintroducing, recovering or maintaining native fauna populations in the wild. Research shows that one of the most effective ways to ensure the survival of many native animals in the wild is to manage introduced predators, including foxes and feral cats. Without this work, the native species protected by the Western Shield program could be lost forever or only found in small, fenced reserves.

Western Shield's work has facilitated increases in the population size and distribution of native species, including the numbat, quokka, western brush wallaby and black-flanked rock wallaby.

Meet the native animals Western Shield protects

Western Shield management benefits over 30 threatened native species. Click through the images below to discover some of these species.

How Western Shield manages the threat of foxes and feral cats to native animals

Western Shield has fauna recovery sites across Western Australia, where it is conserving native wildlife. These occur from Cape Arid National Park on the south coast to Murujuga National Park in the Pilbara, to protecting native species in the forests of the south-west, rangelands and numerous Wheatbelt reserves.

Dryandra Woodland National Park

Dryandra Woodland National Park, spanning over 28,000 hectares, is one of the jewels in the crown for fauna conservation in Western Australia. The woodland comprises a mix of wandoo, mallet and jarrah trees, supporting a rich diversity of native species, including the woylie, numbat, chuditch and malleefowl. DBCA manages foxes and feral cats at this site using baiting and trapping methods. These efforts have seen the recovery of woylie and numbat populations to a point that they are used as source populations for establishing new populations across Australia.

Cape Arid

The Cape Arid Western Shield site, located east of Esperance, encompasses significant portions of Cape Arid National Park and Nuytsland Nature Reserve and is home to the last known wild population of the critically endangered western ground parrot.

Covering over 216,000 hectares, this site consists of coastal sand heaths, low granite hills and saltbush and bluebush woodlands, host to a rich and diverse array of over 1100 plant species and more than 160 bird species. To reduce the threat to the ground parrot and other vulnerable native animal species, DBCA intensively manages foxes and feral cats at this site via aircraft and ground baiting, plus trapping.

Kalbarri National Park

Kalbarri National Park, situated on the Midwest coast of Western Australia, is a significant conservation area home to threatened native species, including chuditch, black-flanked rock wallaby and malleefowl. The chuditch population was reintroduced to the site through translocation in the early 2000s, while the rock wallabies were first translocated in 2016.

Covering over 194,000 hectares, the park surrounds the lower reaches of the Murchison River, which has cut a magnificent 80km gorge through the red and white banded sandstone. This river is critical to wildlife in the area. To protect animal species like the chuditch and rock wallaby, DBCA is managing foxes and feral cats at this site.

Upper Warren

The Upper Warren is an essential part of the Western Shield Manjimup cell comprising of southern jarrah forest. The diversity and abundance of threatened native species, including numbat, chuditch, woylie, western ringtail possum, quokka, tammar wallaby and many more species, makes this site crucial for conserving a wide range of native wildlife in Western Australia. Quite simply, this area is a rich and diverse fauna stronghold. DBCA intensively manages foxes at this site via aircraft and ground baiting. DBCA’s Forest Ecology Research Team is also researching feral cat management and predator-prey relationships in the Upper Warren to inform management of the threat posed by foxes and feral cats.

Management tools

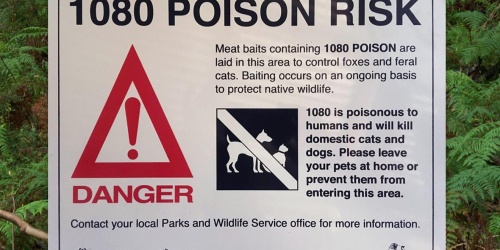

Landscape-scale feral predator management is delivered at these and other fauna recovery sites, primarily through 1080 baiting.

The baiting program is delivered to areas of Western Australia where it is needed most. A prioritisation process is employed to identify key native species based on their conservation status, distribution, vulnerability to introduced predators, and the likelihood of recovery with introduced predator control.

The baiting program is reviewed and adjusted over time to continually improve the outcome for native wildlife.

Other fox and feral cat management methods, including fencing and trapping, are used in specific locations to protect extremely vulnerable native species.

Success stories

Western Shield management has successfully reduced fox numbers in the south-west by over 80% (Marlow et al., 2015). This reduction has facilitated the recovery of numerous native species, including the woylie, chuditch and numbat.

Woylies, chuditch, and brushtail possums have experienced a threefold increase in baited areas of forest compared to areas that are not fox-baited (Wayne et al., 2011).

Once threats like predators are under control, it becomes possible to reintroduce threatened species into areas where they had disappeared.

Since 1996, 140 translocations have been carried out for 27 native animal species, including 20 mammal and five bird species. For instance, from 2016 to 2018, several translocations of rock wallabies were conducted in Kalbarri National Park through partnerships in an intricate logistical operation. Recent monitoring suggests that the initially released rock wallabies have survived well, with their young producing joeys. Consequently, the population is expanding and occupying previously unoccupied cliffs in the gorge.

The role of research

Research and monitoring are fundamental to the delivery of Western Shield. Ongoing work conducted by DBCA aims to identify key knowledge gaps, investigate, assess and enhance the effectiveness of different management strategies, and continuously improve management programs.

Quenda trapping at Ellenbrook. Photo by Ash Millar/DBCA

Meet the predators

European red fox (Vulpes vulpes)

The arrival of the fox in the south-west in the late 1920s coincided with a steep decline in the numbers of smaller native mammals in the southern part of the State. Learn more about the specific challenges of managing foxes in WA and their impact on WA’s biodiversity.

Learn more about the European red fox

Feral cats (Felis catus)

Fox management led to the recovery of several threatened species in the 1990s, however, the impact of feral cats became more prominent. To address this issue, efforts are being made to integrate feral cat management into existing fox management. Learn more about feral cat management challenges in WA, their impact on biodiversity, and DBCA's strategy.

Get involved

| Western shield teaching resources | Western Shield Camera Watch |

The Western Shield Action Pack is a free resource for teachers to help students learn about threatened animal species, the importance of remnant bushland, and how scientists measure biological values. Download the Western Shield Action Pack - Activities on threatened species for Years 4-6 (PDF 10MB) | Get involved with Western Shield! Assist by identifying and classifying animals from images taken by remote cameras in national parks and conservation areas across WA. These camera images aid in monitoring the numbers of foxes and feral cats in an area to inform on-ground management strategies. Learn more about Western Shield - Camera Watch |