The sun is beginning to rise above turquoise seas on a wild and rugged Kimberley island as Mayala man Alec Isaac strolls across the island interior.

Bathed in golden early morning light, he stops at a bush, drops to the ground and begins to dig out its roots. These roots aren’t for eating, but for crushing and putting into tidal ponds. The roots, he says, deoxygenate the water, leaving fish starved of oxygen and easier to catch and eat.

Alec’s Mayala ancestors learned of the roots’ trait and passed on the secret and other cultural stories to their children.

This rich Indigenous culture has remained strong through countless generations, handed down through stories shared around campfires, while riding surging tides to hunt sea creatures and while camping here, on Country, under star- strewn night skies.

Such rich Indigenous heritage and traditional know-how is now earning better recognition and protection thanks to this area’s recent creation as a marine park.

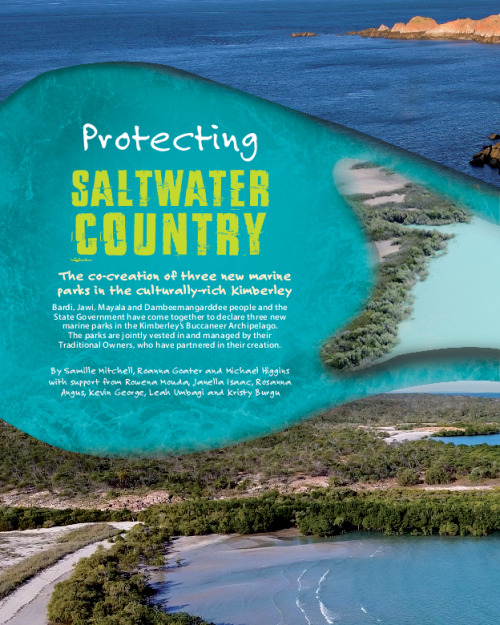

Mayala Marine Park is one of three new marine parks that Traditional Owners and the State Government have created in the Kimberley’s Buccaneer Archipelago. Together, Bardi Jawi Gaarra, Mayala and Maiyalam marine parks protect 660,000 hectares of island-studded seas.

The area’s Traditional Owners jointly manage the parks with Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions staff, helping them to fulfill a cultural obligation to care for Country and do what Traditional Owners have done for tens of thousands of years—coexist sustainably with nature.

Natural bounty

The Buccaneer Archipelago boasts hundreds of rocky isles rising above turquoise seas.

They tower above the ocean in clusters of red rock, embracing white sandy beaches, verdant green mangrove stands, mudflats and rocky cliff faces. In the wet season, mighty waterfalls tumble from the cliffs into the sea.

Fringing reefs have formed around many of the islands, hosting plants and animals that have evolved to tolerate the vast tidal movements. Unlike corals in other areas, the corals here can withstand exposure above the water line during low tides.

Closer to the islands, intertidal reef platforms nurture a myriad of invertebrate life, important cultural resources that Aboriginal people continue to harvest by hand at low tide.

Mangrove-lined creeks and seagrass meadows provide important nurseries for young sea life, including turtles, fish and birds. During different seasons, mammals including dugongs (Dugong dugon), Australian humpback dolphins (Sousa sahulensis), Australian snubfin dolphins (Orcaella heinsohni) and humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) traverse the open seas.

HIGHWAYS ON THE TIDES

If there’s one natural element that characterises this region, it’s the tides. Here, tidal surges of more than 11 metres rush between islands in the biggest tidal movements in Australia. The movement between narrow passages creates tidal streams of up to 10 knots, as well as swirling masses of backwater currents and dangerous whirlpools and tidal overflows.

Despite the tide’s often treacherous nature, Aboriginal people have used tides and currents as highways with great care and skill for millennia. Guided by an intimate knowledge of the tides, currents, seasons and stars, they would ride the tides on double log rafts, between different islands and hunting and harvesting grounds. Different rafts served different purposes—some served best for hunting, others for long ocean journeys in which they’d carry fresh water in baler shells.

BARDI JAWI GAARRA MARINE PARK

Bardi Jawi Gaarra Marine Park embraces the northern stretches of the Dampier Peninsula, north of Broome, and the western islands of the Buccaneer Archipelago. It is home to Bardi and Jawi people, known as gaarra, or saltwater people.

The Bardi and Jawi people have held native title over their traditional lands and seas since 2005. One year later, the Bardi Jawi Rangers group was established to support management of their land and sea Country, Traditional Owners’ livelihoods and connection to Country.

The creation of the jointly-managed marine park builds on their success by providing a marine park management framework, resources, opportunity, and the benefits of partnership with the State Government.

Bardi and Jawi people share traditional stories explaining the creation of the sea, islands, reefs and certain sea creatures.

Through the actions of ancestral beings in the creation period, rai [spirit beings] were placed through Country. Bardi and Jawi people believe that, before birth, they existed as rai. Rai are regarded as good or natural spirits but can cause trouble for strangers who visit or camp in the wrong place or visit areas without being properly introduced.

Bardi Jawi Elder Bugujul, whose Western name is Kevin George, says protecting this culture and Country is not just a personal desire but a cultural obligation.

“The [marine parks] help us Traditional Owners to continue our life in a traditional customary way as well to look after the resources that looked after us, to look after the environment that looked out for us,” he said.

“We have a duty of care and obligation to look after our Country that has been passed on—we have to do this. It has been the wishes of our Elders who have left us, and have left us with this Country. We need to keep that healthy for our future generations.”

MAYALA MARINE PARK

Maiyalam Marine Park adds a further 47,000 hectares to the Kimberley marine reserves. It borders the existing Lalang- gaddam Marine Park in the east of the Buccaneer Archipelago and is managed under the same management plan as Lalang-gaddam.

Maiyalam Marine Park is so named for the word ‘maiyalam’, which means ‘between islands’ or ‘a gap through’ in reference to the sea passages between particularly dramatic and rugged clusters of islands.

The park protects culturally and naturally important areas including the Oobeeyal Special Purpose Zone, which is rich in cultural stories and has long served as a site for traditional fishing and hunting. It’s particularly revered for its culturally important waddaroo [reefs] and jindirm [mangroves] which provide nursery areas for jaiya [fish] and serve as sites for customary activities.

Nearby Garngarngaddaj (Strickland Bay) and Duddgoo (Graveyards) special purpose zones also project sites rich in cultural significance.

Deputy Chair of the Dambimangari Aboriginal Corporation and Dambeemangarddee Traditional Owner Leah Umbagi says being on Country is key to keeping such stories alive.

“When we are on our own Country we feel connected, we feel powerful, we feel rich because everything is around us,” she said.

“The marine park has given us protection of the Country, which is good, and we’re really grateful that we get that protection and our rights and our say on what’s important to the Country.”

CARING FOR COUNTRY—NOW AND IN THE FUTURE

For the Traditional Owners, the new marine parks don’t just protect the natural environment but also cultural history. They support Traditional Owners to co-exist with the land and sea in the way of their forefathers—hunting traditional food, protecting sacred sites and conducting on-Country ceremonies.

This provides opportunity to pass such traditions on to their children, helping to maintain cultural practices and traditions.

Traditional Owners also hope to ensure a brighter future for their people, with new opportunities for culturally and environmentally sensitive tourism, ranger programs and the ability to share this special part of the world with visitors.

With such plans, you get the impression the ancestors would approve. With the sun rising higher in the morning sky, Mayala man Alec Isaac says it’s being here on Country that helps him best connect to the spirit of his ancestors. “I feel closer to them here,” Alec said, patting his heart. “They’re always in my heart and, for some reason, being here, you can feel them, their presence. “[The marine park] will help us keep this area preserved… that’s what they [the ancestors] have been doing for thousands of years.”