Seagrasses are aquatic flowering plants that occupy nearshore coastal areas and shallow banks in estuaries. Seagrass meadows are some of the most productive ecosystems in the world with productivity rates similar to tropical rainforests and coral reefs. Marine and estuarine seagrass communities play vital ecological roles and are estimated to contribute trillions of dollars in ecosystem services each year.

Worldwide, seagrasses are often referred to as ‘ecosystem engineers’, providing essential services to help maintain healthy and productive water systems. They protect coastlines by acting as natural buffers, reducing energy associated with waves, flooding and storm surges. They stabilise the shoreline sediment, preventing erosion and sedimentation, and play an important role in carbon sequestration. Seagrasses also act as ‘coastal filters’, cycling nutrients, cleaning natural water systems and reducing the impacts of pollution. They are essential food resources for megafauna like dugongs and turtles and birdlife like the black swan. They are also hotspots of biodiversity, providing habitat and nursery grounds for fish, crustaceans, and other invertebrate and beneficial bacterial communities.

The Swan-Canning Estuary supports five species of seagrass, with paddleweed (Halophila ovalis) the dominant species. This small seagrass, which gets its name from its oval, paddle-like leaves that are not much bigger than a tablespoon, is a big hitter in the waterway. Halophila communities span an estimated 5.9 square kilometres of the estuary’s soft shallow shoreline, growing in areas less than about 5 metres deep, where sufficient light can reach the riverbed.

Murdoch University Masters students Emily Stout and Ruth Lim spent a year studying invertebrates in the Swan-Canning Estuary. Their work has improved understanding of different invertebrate habitats in the estuary and how they change over time. This research highlights the importance of seagrass habitats, especially those protected within the Swan Estuary Marine Park. Emily determined that Halophila seagrass habitats supported significantly higher species richness and abundance than nearby sand habitats. This was attributed to the complex seagrass rhizosphere, the underground seagrass stem system, providing shelter and a rich source of food.

Vulnerable ecosystems

Despite their importance, the world’s seagrass communities are under threat from many impacts, such as climate change, extreme weather events, dredging, boat propeller scarring, boat moorings, vessel anchoring, eutrophication (the over-enrichment of water bodies) and sedimentation. It is estimated that since 1880 at least 20 per cent of global seagrass areas have been lost, and the rate of loss is predicted to accelerate into the future. The obvious follow-on effect of reduced seagrass meadows is the loss of the important local and global ecosystem services they support.

The Swan-Canning Estuary can be a dynamic environment. Conditions can change rapidly, with high freshwater inputs during flooding events, seasonal algal blooms, tidal changes, anthropogenic influences like development and pollution, and nutrients flowing from a large catchment area that encompasses metropolitan and agricultural landscapes. This makes the Swan-Canning Estuary, and particularly the Halophila meadows within it, more susceptible to change and degradation than coastal environments. Two relatively recent climatic events that impacted seagrass communities in the estuary demonstrated this vulnerability.

- An extreme flood event in February 2017 during the peak seagrass growth period increased water temperatures while decreasing salinity and light. This resulted in reduced Halophila biomass and leaf density. Full seagrass meadow recovery did not occur until 11 months after the event.

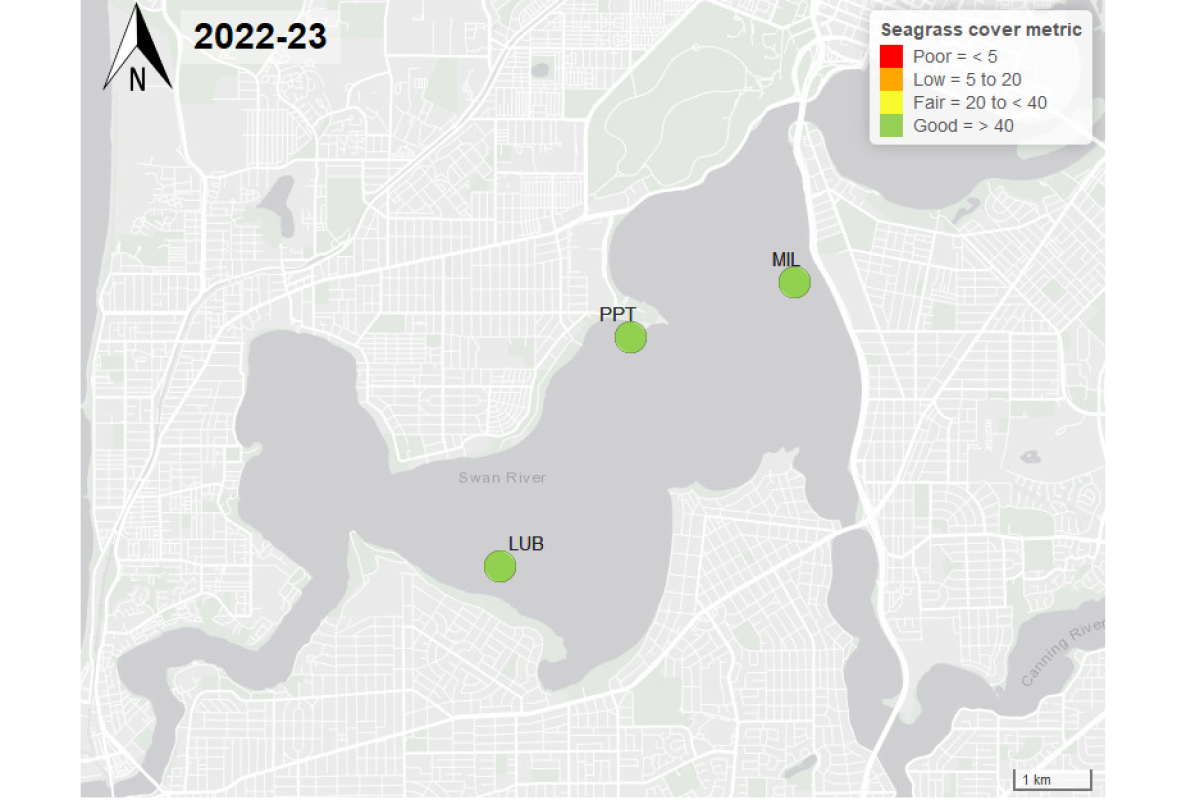

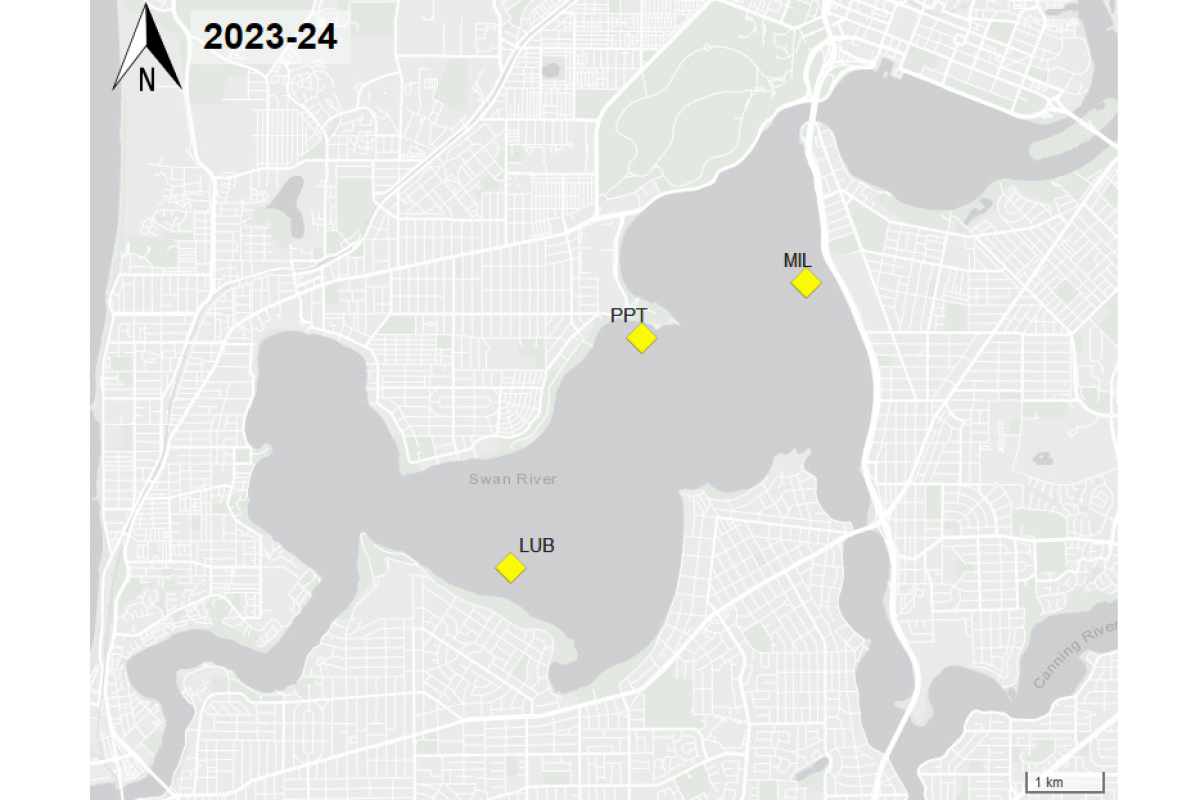

- A heat wave affecting Perth in the summer of 2023–24, combined with low tides, left large areas of shallow seagrass meadows exposed to high air temperatures. In combination, low tides and high temperatures can lead to drying of the leaves and potential loss of seagrass meadows. This resulted in a continued level of ‘fair’ seagrass cover at three sites in the estuary in 2024–25 (seagrass cover measured within each quadrat and averaged across all sampling months was between 20–40 per cent, Figure 1).

These unusual climatic events highlight the importance of monitoring seagrass health and allow managers to gain an understanding of how the meadows will respond, recover and persist in an uncertain future.

Monitoring seagrass – the value of volunteer effort

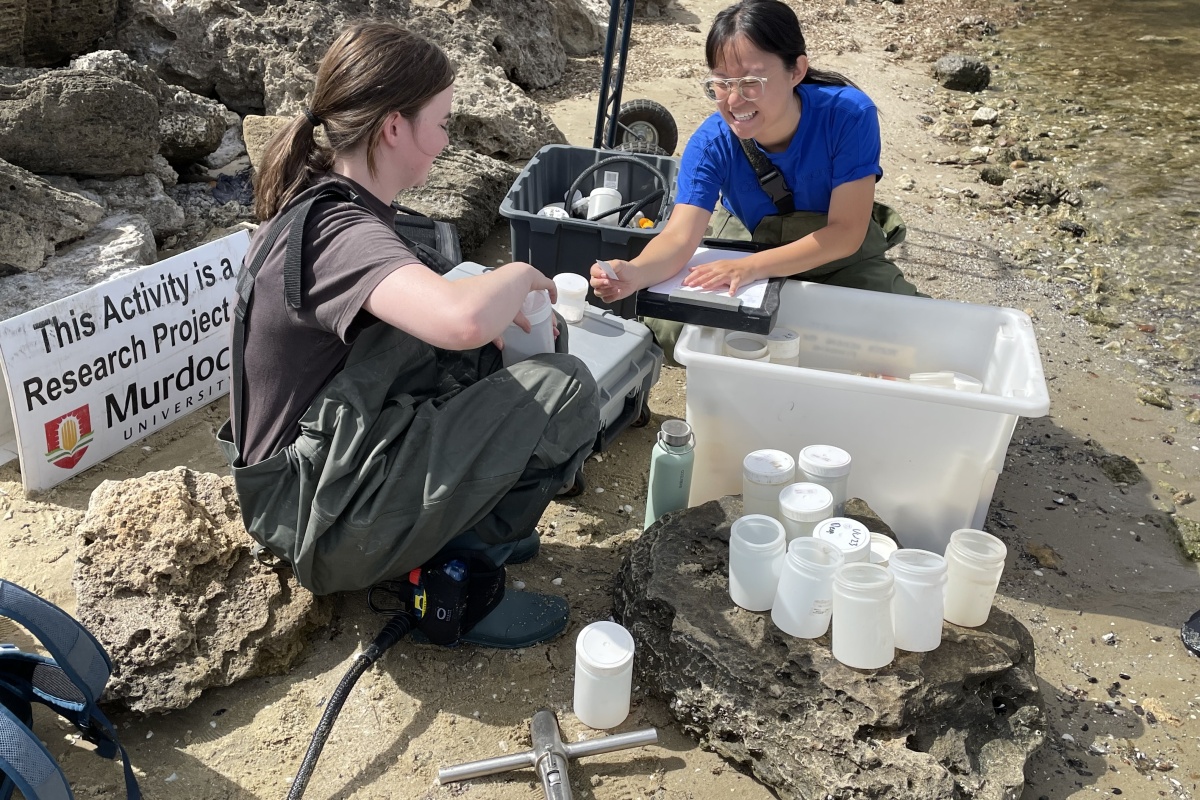

DBCA’s Rivers and Estuaries Science team monitors seagrass from November to March every year, providing data to report on ecosystem health and seagrass distribution in the estuary. Joining forces with an invaluable group of volunteers during spring and summer, the team wades through the water at six monitoring sites within the estuary to conduct quadrat and core surveys. The aim is to measure seagrass cover and observe the condition of the seagrass first-hand (Figure 1). Back in the laboratory, a team of volunteers sifts through the seagrass, sorting and taking records of leaf, flower, fruit and seed numbers.

Volunteers also ‘adopt’ two light loggers at each site and every week, monitor and maintain them to ensure they are functioning at all times. This is a critical role, since these loggers are vital to record how light is hitting the seagrass and gauge photosynthesis levels in the meadows. Volunteers come from all walks of life, including university students, interested local residents and retirees looking for ways to contribute to the environment. Volunteer contributions are highly valued and play an important role in supporting the DBCA’s determination of overall seagrass performance, a vital index used in reporting on overall seagrass health.

Preserving habitat and ecosystem services

The Swan Estuary Marine Park is an A-class reserve that was declared in 1990 to provide protection for local and migratory birds and their habitat. The marine park is divided into three zones: Alfred Cove (200 hectares), Pelican Point (45 hectares) and Milyu (95 hectares) (Figure 2). Together these zones cover 40.2 per cent of the seagrass habitat within the Swan-Canning Estuary, conserving these critical habitats for the many ecosystem services they provide and the species that rely on them, including birds, fishes and invertebrates.