Baudin's cockatoo (Photo: Rick Dawson/DBCA)

Have you seen a threatened or priority listed animal?

Report sightings of threatened and priority fauna, other specially protected animals, and migratory birds protected under international agreement by sending us an email or completing a report form.

The report form may also be used to record unusual observations of common animals, such as where an animal is found outside of its usual range.

Threatened and priority fauna (animal) report form

If you are unsure if you have correctly identified an animal, take a photograph, not a specimen.

Licences are required for the taking of native wildlife in Western Australia.

Under the Biodiversity Conservation Act, specific authorisation, separate to a licence, is required to take or disturb threatened fauna. However, providing first aid or emergency care is permitted.

Send report forms to:

Species and Communities Program

Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions

Locked Bag 104,

Bentley Delivery Centre WA 6983

or email it to fauna.data@dbca.wa.gov.au

Protocols for monitoring threatened animals

The following manual provides guidance on the establishment of monitoring programs for animals. Refer to the Standard Operating Procedures on the animal ethics page for further information on fauna survey and monitoring techniques.

Our threatened species often require a species-specific approach.

Below you will find some helpful information for designing surveys, environmental impact assessments, conservation projects, and recovery initiatives.

Arid bronze azure butterfly

The arid bronze azure butterfly (Ogyris subterrestris petrina; ABAB) is a threatened species that is listed as critically endangered under the national Environment Protection and Biodiversity Protection Act 1999 and the state Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016. The ABAB is listed due to its severely fragmented distribution with only two extant subpopulations being recorded in Western Australia. These subpopulations are at Barbalin Nature Reserve (BNR), and at a second site approximately 100km from Barbalin. This second site is small and its precise location is withheld for conservation reasons. A third subpopulation (the first discovered, in the 1980s) occurred near Lake Douglas, 12km SW of Kalgoorlie, but is now locally extinct and no ABAB have been recorded there since 1993.

Surveys for the ABAB may be required in WA where development or land management activities are proposed that could potentially affect the species and/or habitat suitable for the species. A survey guideline document has been prepared that provides guidelines for detecting current presence, or asserting the absence of the ABAB, and assessing the importance of the habitat proposed to be impacted.

The ABAB is a medium sized (wingspan ~36mm) robust butterfly capable of rapid flight. It is slightly smaller than the common 'cabbage white' butterfly (wingspan ~44mm). It is predominately dark grey-brown to black, with bronze to purple-bronze coloration on the upper-sides of the wings. The underside is grey-brown with iridescent bluish-white bars in the forewing cell and a series of brown-black markings on the hind wing. It is sexually dimorphic, with males having a dull dark purplish-bronze upper side whereas females have purplish areas on the upper sides of both wings and a distinctive cream patch on the forewing (Figure 1).

The ABAB has an obligate association with a sugar ant Camponotus sp. nr. terebrans. The ABAB’s larvae live entirely within the ant’s nest during their development. The ants protect the larvae from predators and are thought to be rewarded with secretions produced by the larvae. The most critical factor for habitat occupancy by the butterfly is the presence of large colonies of the host ant; only large colonies can support the ABAB because, being a parasitic species, it requires large numbers of hosts. The potential distribution is extensive and encompasses much of the semi-arid zone (rainfall < 325mm) south of approximately 26o S latitude (Map 1)

The ABAB may be identified by several distinctive features:

- Unique very dark colouration (adults, especially males, appear almost black in flight)

- a habit of perching on the ground in open areas (including on roads and roadsides)

- a very rapid and direct flight pattern which is characteristic of the genus, and

- being amongst the largest lycaenid butterflies in Australia.

Many flowering plants of the lower, mid and upper storey are likely to be nectar sources for the adult ABAB. In woodland such as at the BNR site, many plants such as Eucalyptus, Acacia, Grevillea, Hakea, and annual species would be probable nectar plants. Nectar is likely to peak in availability during September–October, which is also the main butterfly activity (flying) period.

Eggs are laid on small stones or bark near ground level, and hatch in around 1-2 weeks. The newly hatched larvae either crawl or are carried into the ant nest. The feeding habitat for the larvae is the subterranean galleries of the sugar ant Camponotus sp. nr. terebrans. Larvae of ABAB are wholly dependent on the ants, feeding either on the immature stages of the ants or on ant regurgitations (Braby, 2000). The myrmecophilous larvae are either parasites (feeding on the ant brood) or 'cuckoos' (being fed regurgitated food by the ants). The length of the life cycle is unknown - in warmer months it may be as short as six weeks, but development time may be 6-12 months over winter.

The early stages (eggs, larvae and pupae) are difficult to detect - only two larvae and a single pupa have ever been found. The eggs are small (1.0mm diameter) and are laid in clusters of approximately 2-20 (average 8) at the base of suitable trees (i.e. those with an active ant colony). They are typically laid on the northern and western sides of the tree base, typically during the middle of the day when the ants are inactive. Hatched eggs may persist in situ for several years (Field 1999). Surveys to determine if the ABAB occurs at a site therefore rely on detecting the presence of the adult butterfly (although experienced observers may be able to locate eggs or egg cases to determine ABAB presence).

Habitat

At the two known extant sites where the ABAB occurs, the vegetation is mature mixed gimlet E. salubris/ salmon gum E. salmonophloia woodlands on red-brown loam soils, with an open understorey. In addition to gimlet and salmon gum, other smooth-barked eucalyptus at these sites which have basal ant colonies include wandooE. capilosa subsp. wandoo, smooth-barked york gumE. loxophleba subsp. lissophloia and ribbon-barked mallee E. sheathiana. The habitat at the locally extinct Lake Douglas site differs from the other sites, but is also dominated by mature smooth-barked eucalypt woodland, particularly Victoria Desert Mallee Eucalyptus concinna.

Host ant

Camponotus sp. nr. terebrans is a widespread but generally uncommon ant that occurs within inland southern Australia, including the northern and eastern wheatbelt and pastoral zone. Previously it was included in the species Camponotus terebrans Lowne, but recognised as a distinct form (the 'northern' form in McArthur et al. 1997 and the 'undescribed pale species' in Andersen 2007). It has distinct morphological and genetic differences from Camponotus terebrans sensu stricto and is now recognised as a separate species. As it has not yet been formally described as a new species, it is currently referred to as ' Camponotus sp. nr. terebrans' because of its similarity to that species. McArthur et al. 1997 give a detailed description of the host ant and this paper should be consulted to assist in identifying the ant (see https://www.publish.csiro.au/zo/ZO97055 ). Some further information is provided in Andersen (1997; p.34), and Heterick (2009) provides a key to the ant species of south-western Australia and some additional information about the species (pp.85-86).

Camponotus sp. nr. terebrans has been recorded at several sites within the semi-arid zone (rainfall <325mm), south of approximately 26o S latitude. The ant is more common in South Australia, western NSW and north-western Victoria (where it hosts the eastern subspecies Ogyris subterrestris subterrestris). At many of the previously recorded sites in WA the ant is no longer extant – it appears to colonise a site, thrive for some years (perhaps decades), but ultimately die out. It is currently (2020) known to be extant at three large and several small colonies. Two of the three large colonies are where the ABAB also occurs. The third large ant colony is located in mixed salmon gum/gimlet woodland on both sides of Dunbar Rd (50J 0734203 E; 6481024 S), 35 km south of Marvel Loch. All three of the large colonies occur in mature woodland, whereas the smaller colonies are in younger regrowth.

The ant is one of the first ants to colonise disturbed areas. They make their largest nests at the base of eucalypt trees and these are sometimes apparent from a large amount of excavated soil. Workers display wide variation in size, colour, pilosity and profile, and because of this variation, major (large) and minor (small) workers may be misidentified as different species if collected away from the nest. As well as hosting the larvae of the ABAB, the ants also host leafhoppers ( Pogonoscopus lenis) within their nests, in another symbiotic relationship.

References and future reading

Andersen, A.N., 2007. Ant diversity in arid Australia: a systematic overview, In: Advances in ant systematics (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): homage to E. O. Wilson – 50 years of contributions . Eds. R.R. Snelling, B. L. Fisher, and P. S. Ward, pp. 19-51. Memoirs of the American Entomological Institute.

Bishop, C., Williams, M.R., Mitchell, D., Gamblin,T. 2010. Survey guidelines for the Graceful sun-moth (Synemon gratiosa) & site habitat assessments. Version 1.2 Science Division and Swan Region, Department of Environment and Conservation.

Braby, M.F., 2000. The butterflies of Australia: their identification, biology and distribution . CSIRO publishing, Collingwood, VIC.

Braby, M.F., 2016. T he complete field guide to butterflies of Australia. 2nd edn. CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, VIC.

Department of the Environment, 2015. Conservation adviceOgyris subterrestris petrina Arid bronze azure (a butterfly) . In: Species Profile and Threats Database, Department of the Environment, Canberra.

Field, R.P., 1999. A new species of Ogyris Angas (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae) from southern arid Australia. Memoirs of Museum Victoria 57: 251-259.

Gamblin, T., Williams, M.R., Williams, A.A.E. 2010. The ant, the butterfly, the leafhopper and the bulldozer. Landscope 21(2) : 55-58

McArthur, A. J., Adams, M. and Shattuck, S. O. (1997) A Morphological and Molecular Review of Camponotus terebrans (Lowne) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Australian Journal of Zoology 45 :579-598.

Schmidt, D.J., Grund, R., Williams, M.R., Hughes, J.M. 2014. Australian parasitic Ogyris butterflies: east–west divergence of highly-specialized relicts. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 111: 473-484.

Williams, A., Williams, M. 2005. Endangered or extinct?: Kalgoorlie's arid bronze azure. Landscope 21(2): 19-23

Williams, M.R., Atkins, A.F., Hay, R.W., Bollam, H.H. 1992. The life history of Ogyris otanes C. & R. Felder in the Stirling Range, Western Australia (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae). Australian Entomological Magazine 19: 55-60.

Williams, M.R., Hay, R.W. 2001. Two new subspecies of Ogyris otanes C. & R. Felder (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae) from Western Australia. Australian Entomologist 28: 55-63.

Williams, M.R. and Williams, A.A.E. 2008. Threats to the critically endangered Arid Bronze Azure butterfly ( Ogyris subterrestris petrina) by proposed vegetation clearing. DEC Internal report, Nov 2008, 17 pp.

Williams, A., Williams, M., Powell, R., Walker, G. 2012. Rare butterflies of the south-west. Department of Environment and Conservation, Kensington Western Australia.

Bilby

The bilby (Macrotis lagotis) is a medium-sized marsupial that is best known for its rabbit-like ears. It has long, silky blue-grey fur and a long tail that is black with a white tip. The bilby is light and delicate in build but with strongly clawed toes for digging burrows.

Bilbies are solitary, nocturnal animals, spending daylight hours in their deep, spiral shaped burrows and emerging at night to forage for plant roots, bulbs, fungi, grass seeds, termites, ants, beetles, insect larvae and spiders.

Dalgyte and Ninu are just two of the many Indigenous names for the bilby. It is also commonly known as the greater bilby, to differentiate it from the extinct lesser bilby Macrotis leucra.

The bilby is a threatened species under State and Commonwealth legislation. In Western Australia, the species is listed as Vulnerable fauna under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016. Nationally it is also listed as Vulnerable under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 and internationally is on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species as Vulnerable.

Report any sightings of bilbies by sending an email or a fauna report form, with a photo of the animal, if you have one, to fauna@dbca.wa.gov.au.

Where are bilbies found?

Historically, the bilby was found across most of the arid and semi-arid areas of mainland Australia. Since European settlement, the species has experienced a large decline. In Western Australia, it is now restricted to the Gibson, Little Sandy and Great Sandy Deserts, and parts of the Pilbara, Dampierland, Central Kimberley and Ord-Victoria Plains bioregions. It also occurs across to the Tanami Desert in the Northern Territory, and there are disjunct subpopulations in the Channel Country and Mitchell Grass Downs bioregions in Queensland.

The bilby continues to occupy a wide range of vegetation types, with the major vegetation types defines as:

- open tussock grassland on uplands and hills,

- mulga woodland/shrubland growing on ridges and rises, and

- hummock grassland (spinifex) growing on sandplains and dunes, drainage systems, salt lake systems and other alluvial areas.

Refer to NatureMap for further information regarding the distribution of this species.

Main threats to bilbies

- predation by foxes, feral cat and wild dogs

- competition with, and habitat degradation by, introduced herbivores (rabbits, cattle, camel)

- inappropriate fire regimes

- climate change leading to a drier climate

- habitat loss and degradation due to mining and other developments

- road mortality

Recovery plan

Pavey, C. (2006). National Recovery Plan for the Greater Bilby (Macrotis lagostis). Northern Territory: Department of Natural Resources, Environment and the Arts.

The Recovery Plan outlines actions that are being implemented to improve the conservation status of the bilby:

- reduce the impact of predation by foxes, wild dogs and feral cats

- maintain genetic diversity.

- conduct reintroductions within the species' former range.

- monitor trends in occurence and abundance.

- sssess the impact of predators, fire and other threatening processes.

- raise community awareness and involve stakeholders in the recovery process.

The National Bilby Recovery Team, with membership including the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, was re-established in 2016 to guide the recovery actions undertaken for bilby conservation.

Current bilby research

The Department is the key agent undertaking research on the bilby in Western Australia, with a focus on improving ecological and distributional information to inform adaptive management practices.

The Pilbara bilby research program, funded by environmental offsets derived from resource development, is supported by several mining companies, environmental consultancies, CSIRO and traditional owner groups.

A coordinated Kimberley bilby program is being established, and will build on the existing work of WWF, Environs Kimberly, Rangeland NRM, Kimberley Land Council and numerous traditional owner ranger groups. Both programs are focusing on bilby distributional survey, population monitoring and adaptive threat abatement activities at a landscape scale.

Successful reintroductions have been undertaken in South Australia, New South Wales, Western Australia and Queensland, including into fenced enclosures and onto islands. A national captive breeding program, as part of a Zoo and Aquarium Association conservation program, has been running since 1995.

Bilby surveys

Surveys for the threatened greater bilby may be required in WA where development or land management activities are proposed that could potentially affect the species and/or habitat suitable for the species. Guidelines have been developed for detecting current or recent presence, or asserting the absence of bilbies, and assessing the importance of the habitat proposed to be impacted. The latest version of the guidelines and a datasheet are provided below. Please note that these guidelines will be subject to change as new information about bilbies becomes available.

Further information

EPBC Act SPRAT profile - Macrotis lagostis Greater Bilby

Bradley, K., Lees, C., Lundie-Jenkins, G., Copley, P., Paltridge, R., Dziminski, M., Southgate, R., Nally, S. & Kemp, L. (Eds.) (2015). 2015 Greater Bilby Conservation Summit and Interim Conservation Plan; an initiative of the Save the Bilby Fund. Minnesota, USA: IUCN SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group.–

Black cockatoos

Black cockatoos, belonging to the Calyptorhynchus and Zanda genus, are large, black-feathered cockatoos that have loud, distinctive calls and are most often observed flying and feeding in small to large flocks. There are three threatened species of black cockatoo that are found in Western Australia:

- Carnaby’s cockatoo (Zanda latirostris, previously Calyptorhynchus latirostris) is one of two species of white-tailed black cockatoo found in south-west WA.

- Baudin’s cockatoo (Zanda baudinii, previously Calyptorhynchus baudinii) is the other white-tailed black cockatoo found in south-west WA.

- Forest red-tailed black cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus banksii naso) is one of three subspecies of red-tailed black cockatoo and it is found in south-west WA. The two other subspecies of red-tailed black cockatoos in WA are not threatened: C. b. banksii is found in the Kimberley, and C. b. escondidus found in the Pilbara, Midwest and Wheatbelt.

Artificial hollows

Artificial hollows can be used to help conserve these threatened black cockatoos by enabling them to breed in areas where natural hollows are limited. The fauna note below provides advice on how to select an appropriate site, guidelines on how to design and place artificial hollows, and advice on how to maintain and monitor artificial hollows.

DBCA now maintains a register of artificial hollows. This will enable future research to improve our understanding of use and the extent to which factors such as placement and maintenance affect breeding success for all three species of black cockatoo. The fauna note has been updated to include instructions on how to report the installation of a hollow and document any monitoring or maintenance activities using the black cockatoos artificial hollow register template available below. The information presented here is based on experience with Carnaby’s cockatoo which have many examples of successful use of artificial hollows. Forest red-tailed black cockatoos have a few known examples of use but appear to rarely use artificial hollows. While there are currently no confirmed records of Baudin’s cockatoo using artificial nest hollows, gathering information on the use of artificial hollows is important to contribute to ongoing management.

Black cockatoos and orchards

Birds can cause significant damage to fruit and nut orchards. In most cases the damage level is low, but it can vary depending on the property, region, year and orchard crop.

The below are intended to help fruit and nut growers, residents and local government authorities manage fruit and nut damage by black cockatoos. They have been developed in accordance with a commitment to protect threatened bird species, the viability of the fruit growing industry and the welfare and amenity of residents.

These guidelines apply specifically to situations where the bird species causing damage is listed as threatened under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 (BC Act).

Night parrot

The night parrot (Pezoporus occidentalis) is a small, elusive parrot endemic to Australia. It is 22-25 cm long, short-tailed and dumpy in appearance. Adults are mostly green with extensive black and yellow markings, and a yellow belly. Night parrots are highly cryptic in nature – they are nocturnal, ground-feeding parrots that inhabit remote arid and semi-arid areas of Australia.

Where are night parrots found?

Historically, night parrots have been reported from arid and semi-arid regions of Western Australia, Queensland, South Australia, New South Wales, Victoria and the Northern Territory.

Records of night parrots over the last century are scant. Because the species is highly cryptic, it has been difficult to obtain convincing proof of its current presence, though there have been persuasive ongoing reports. In 1990 and 2006, two dead specimens were found in western Queensland. Accepted sightings have been recorded from near Fortescue Marsh in the Pilbara in 2005 and near Wiluna in the Goldfields over the last decade. In 2013, a population of night parrots was rediscovered and subsequently intensively studied in western Queensland, revealing much about their ecology. In March 2017 a population was observed and photographed at an interior salt lake in central Western Australia. Since then, a number of additional populations have been confirmed in desert areas in Western Australia.

Night parrot roosting and nesting sites are in clumps of dense vegetation, primarily old and large spinifex (Triodia) clumps, but sometimes other vegetation types. Often the vegetation in these habitats will be naturally fragmented and therefore well protected from fire. Little is known about foraging sites, but favoured sites are likely to vary across the range of the species. In Queensland, night parrots have been shown to feed in areas rich in herbs including forbs, grasses and grass-like plants, and it is likely that such areas may also be important in Western Australia. Triodia is likely also to provide a good food resource for night parrots, in times of mass flowering and seeding, but they also rely heavily on a range of other food species. Sclerolaena has been shown to be a source of food and moisture.

Main threats to night parrots

Little is known about the threats to night parrots and they are likely to vary across its range. Suspected threats include:

- Inappropriate fire regimes (frequent and/or widespread fires)

- Moderate/heavy grazing by domestic or feral herbivores (noting that some populations of night parrots have been found to persist in areas of low levels of grazing by cattle in both Queensland and Western Australia)

- Predation by feral cats

- Loss or degradation of habitat by disturbance or development activities including mining and associated infrastructure / related activities

- Climate change (increasing temperatures will increase the need to find water or succulent (55% water) food during summer and risk of fire).

Night parrot surveys

Given the apparent rarity and specific habitat requirements of the night parrot, surveys in suitable areas of Western Australia that may be proposed for significant disturbance activities are likely to be necessary to determine their presence, population size and distribution. This will assist in preventing night parrot populations from being significantly negatively impacted before their distribution and ecological requirements are properly understood.

A guideline has been developed based on the best available knowledge to assist in determining when night parrot surveys may be required and the appropriate methods for survey in Western Australia. The latest version of the guideline is provided below. Please note that this guideline will be subject to change as new information about night parrots becomes available.

Any surveys for night parrots should be reported to DBCA (fauna.data@dbca.wa.gov.au), including when night parrots are not detected from targeted surveys, so that knowledge can be built up about the likely distribution of this species, its habitat and the optimal survey methodology. Similarly, any sightings outside of formal surveys should also be reported to this address.

Current night parrot research

Detailed research on the biology and ecology of night parrots is being undertaken in Queensland. Currently, the highest research priority in Western Australia is survey to determine the extent and abundance of the species in this state.

Further information

- EPBC SPRAT profile – Night Parrot

- Threatened Species Scientific Committee (2016). Conservation Advice Pezoporus occidentalis Night Parrot. Department of the Environment, Canberra, ACT.

- The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species profile – Night Parrot

Western ground parrot

Western ground parrot. Photo by Alan Danks/DBCA

Western ground parrots (Pezoporus flaviventris), known as Kyloriny by the Noongar Aboriginal people, are medium-sized, slim and mostly green parrots that are rarely seen because they spend most of their time on the ground amongst the vegetation. Bushfires in 2015 and 2019 burnt the majority of the birds’ known habitat in Cape Arid National Park and Nuytsland Nature Reserve, further threatening the species’ already uncertain future. There are thought to be no more than 150 birds left in the wild.

The western ground parrot is a threatened species under State and Commonwealth legislation. In Western Australia the species is listed as Critically Endangered fauna under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016. Nationally it is also listed as Critically Endangered under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.

DBCA are now using ‘Kyloriny’ as the spelling for the Minang Noongar pronunciation of ‘Kyloring’. The use of the ‘y’ softens the ‘ing’ sound, Knowledge shared with us by Elders at the Structured Decision Making (SDM) workshop held in Albany in June 2024.

Where Western ground parrots are found

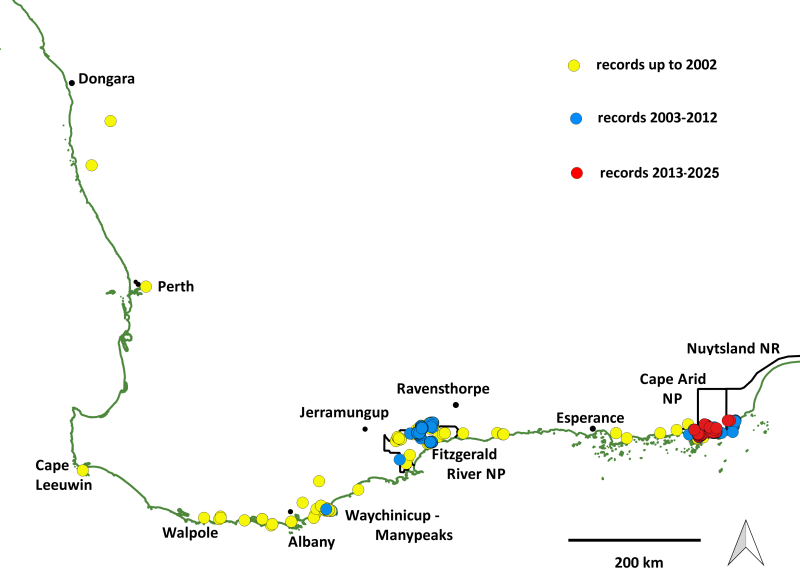

A map of the known historical distribution of western ground parrots. Of the records from Perth northwards, some have poor spatial and temporal resolution, and some are unconfirmed

Typically, western ground parrots (WGP) are found in low, mid-dense heathland within a few tens of kilometres of the south coast of Western Australia. Historically, they were known to exist along the south coast between Cape Leeuwin and Point Malcolm, 180km east of Esperance, and north along the west coast to Dongara. Threats have caused major declines in range and population size, with the species disappearing in more recent times from Waychinicup-Manypeaks and Fitzgerald River National Park.

Today the species is only found in the south-eastern part of Cape Arid National Park and adjacent areas of Nuytsland Nature Reserve. However, between 2021 and 2023, small numbers of birds were translocated to an area east of Albany, where the species was known to occur historically. This translocation is an attempt to increase the number of populations to reduce the risk of bushfire having a catastrophic impact on the species. Although it is too soon to know whether the translocation will result in the establishment of a second population, the early results are looking promising highlighted by the detection of juvenile calls on ARUs. This indicates that breeding has occurred at the translocation site.

How to spot a western ground parrot

Western ground parrots are almost impossible to see, not only because there are so few of them left, but also because they spend the majority of their time feeding, resting and nesting on the ground in low, dense heathlands. If flushed, they will fly very low over the vegetation before diving back down for cover. Experts involved in survey work have found that listening for their calls in the hour before sunrise and in the hour after sunset is the best technique for detecting WGPs. The calls are best described as a series of high-pitched whistles, often likened to a boiling kettle. Current survey techniques use sound recording devices to detect WGPs.

The Western ground parrot information sheet will assist in determining if you have seen a WGP, or one of the other parrots with which they are frequently confused.

If you still think you have seen a WGP after reading the information sheet, we would really like to hear about it. To report a sighting, please contact the department’s Albany District Office on (08) 9842 4500, or email details to sarah.comer@dbca.wa.gov.au and albany@dbca.wa.gov.au. In addition, we ask that you also fill out a fauna report form and email it to fauna.data@dbca.wa.gov.au.

Main threats to the western ground parrot

- historical habitat clearing for agriculture

- frequent and extensive bushfires

- predation by feral cats and foxes

- climate change leading to an increase in dry lightning storms and bushfires, and changes to habitat suitability and food availability

Refer to the South Coast Threatened Birds Recovery Plan for further information on threats to the western ground parrot.

Recovery Plan

The Recovery Plan outlines actions that are being implemented to improve the conservation status of a number of threatened birds in the south coast region, including the western ground parrot:

- refine, locate and map areas of habitat critical to survival

- manage habitat and threats

- develop survey and monitoring protocols to improve detection of population changes

- monitor and survey known sites and suitable habitat

- develop a translocation and captive breeding program

- raise community awareness and involvement

Recovery projects

The South Coast Threatened Birds Recovery Team, with members including scientists, conservation organisations, community groups, NGOs and the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, is an advisory group that assists the Department with implementing the actions outlined in the South Coast Threatened Birds Recovery Plan.

The Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions takes the lead role in implementing the recovery actions for the WGP. More details on the efforts being made to save the WGP are provided in the western ground parrot information sheet.

Perth Zoo houses a small number of WGPs to refine husbandry techniques with the aim of determining if captive breeding is a viable solution for the conservation of this species.

South Coast Natural Resource Management and Birdlife Australia support the implementation of recovery actions for the western ground parrot and other threatened species through seeking funding and raising awareness. BirdLife Australia has a project officer based in DBCA’s Albany office, which assists with conservation management of South Coast Threatened Birds.

Acknowledgement is given to the community groups and individuals who dedicate their time and energy to the conservation of the WGP. Friends of the Western Ground Parrot raises funds and awareness, assists with research and recovery projects, and lobbies for government support.

In March 2016, conservation experts attended a workshop hosted by the then Department of Parks and Wildlife. A total of 39 delegates from 19 organisations met over three days to discuss the WGP and develop recommendations for future conservation efforts. The event was supported by WWF Australia, BirdLife Australia, the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program, South Coast NRM and Friends of the Western Ground Parrot. You can read more about the workshop and its outcomes in the workshop report below.

Further information

- Department of Parks and Wildlife (2014). South Coast Threatened Birds Recovery Plan. Perth, Western Australia: Department of Parks and Wildlife.

- Garnett, S. T., and Baker, G. B. (Eds.) (2021). ‘Action Plan for Australian Birds 2020’. (CSIRO Publishing: Melbourne, Victoria.)

- EPBC Act SPRAT Profile – Pezoporus flaviventris - Western Ground Parrot, Kyloring

- BirdLife Australia has an information webpage about the species.

- The Friends of the Western Ground Parrot website and Western Ground Parrot history blog has historical information and further facts about the western ground parrot.

- ABC’s Landline program produced a video about the WGP translocation.

- Jennene Riggs/Riggs Australia produced a documentary on the WGP called Secrets at Sunrise, and have a YouTube channel featuring a series of short videos about the WGP

- Both Landscope and Western Australian Bird Notes have published articles about the western ground parrot;

- Comer, S., Burbidge, A.H., Algar, D., Berryman, A. & Bondin, A. (2013). Kyloring, cats and conservation: the race to save the western ground parrot. Landscope 29(2): 40-45.

- Comer, S., Burbidge, A.H., Algar, D., Clausen, L., Berryman, A., Pinder, J., Cowen, S., Danks, A., Pridham, J. & Butler, S. (2016). From the ashes: Creating a future for western ground parrots. Landscope 31(4): 11-15.

- Comer, S. & Burbidge, A.H. (2016). A catastrophic start to the fire season for threatened birds on the South Coast Western Australian Bird Notes 157: 4-5.

- Bondin, A. (2016). Western Ground Parrot - another victim of the Esperance fires. Western Australian Bird Notes 157, 20–21.

- Bondin, A. (2019). Lightning never strikes twice - renewed fears for the Western Ground Parrot. Western Australian Bird Notes 169, 18–19.

- Comer, S., Burbidge, A., Mair, G., and Butler, S. (2019). Bushfire impacts Western Ground Parrots - again. Western Australian Bird Notes 169, 19–20.

- Stokes, H., Stokes, V., and Comer, S. (2021). A new home for kyloring: the first phase of a wild-to-wild translocation completed. Western Australian Bird Notes 179, 1, 4–6.

- Comer, S., Burbidge, A., Berryman, A., Thomas, A., Blythman, M., Stokes, H., and Ford, S. (2021). A new chapter for kyloring. Landscope 37(1), 18–22.

- Ferguson, A., Berryman, A., Bradfield, K., Comer, S., and Burbidge, A. (2024). Unravelling the mysteries of kyloring, the Western Ground Parrot. Western Australian Bird Notes 189, 4–7.

- Wettin, P. (2024). Western Ground Parrot: Fresh hope for survival of WA’s rarest bird. Western Australian Bird Notes 191, 10.

Western ringtail possum

The western ringtail possum (Pseudocheirus occidentalis) is a small to medium sized leaf-eating arboreal marsupial, with adults weighing approximately 700g to 1.3kg, a head/body length of 30-40cm and a tail as long as its body. Its tail is strongly prehensile which is used to support the possum while foraging in the tree canopy.

The western ringtail possum is a threatened species under State and Commonwealth legislation. In Western Australia the species is listed as Critically Endangered fauna under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016. Nationally it is also listed as Critically Endangered under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, and internationally is on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species as Critically Endangered.

Where are western ringtail possums found?

Western ringtail possums are only found in the south-west of Western Australia. They can be found as far north as Dawesville near Mandurah extending down the coast from Bunbury to the Leeuwin-Naturaliste National Park, in the Upper Warren area near Manjimup and east to Waychinicup National Park near Albany.

The western ringtail possum is a shy animal that is rarely seen on the ground unlike its more regularly encountered relative, the common brushtail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula). Ringtails spend most of their time in trees (arboreal), particularly in the canopy of peppermint (Agonis flexuosa) woodland and eucalypt forests. They feed on leaves and like to forage for food at night (nocturnal). They build nests or resting places called ‘dreys’ from the foliage and also use tree hollows.

In urban areas ringtail possums will live in roof spaces of houses, sheds and other buildings and eat garden plants including roses and fruit trees.

How to spot a western ringtail possum

The western ringtail possum is characterised by its dark brown fur with a cream or grey chest and stomach, short rounded ears and very long, thin, white-tipped tail, with very short hair on the tail. A white tip on the tail is not a distinguishing feature for a ringtail possum as brushtail possums can also have a white-tipped tail as shown in the photos below. Brushtail possums can have a very bushy tail or a tail with hair that is the same length as the rest of the body, and the tail tip can be black or white. Both the ringtail and brushtail possum can curl their tails into a ring-like shape to hold on to branches.

What are the main threats to the western ringtail possum?

- Habitat destruction and fragmentation

- Predation by introduced predators (foxes and feral cats)

- Death by car strike and domestic pets

- Altered fire regimes and the effects of drought

How you can help?

Report sightings of western ringtail possums by sending us a fauna report form

If you think you have western ringtail possums living in your area there are a few things you can do to help conserve this species:

- Drive carefully to avoid vehicle strikes, particularly at night

- Retain and plant peppermint trees which are an important food item

- Avoid chemicals and baits that can be harmful to possums

- Keep domestic pets contained, particularly at night

- Do not feed possums

Recovery plan and habitat assessment

Department of Parks and Wildlife (2017). Western Ringtail Possum (Pseudocheirus occidentalis) Recovery Plan. Wildlife Management Program No. 58. Department of Parks and Wildlife, Perth, WA.

Western ringtail possum - Western Ringtail Possum Recovery Team

In 2017 the western ringtail possum recovery plan was updated coinciding with a reassessment of the conservation of the species leading to a threat status assignment of Critically Endangered using IUCN criteria. To support the implementation of the recovery plan, the Western Ringtail Possum Recovery Team also reconvened in 2017 after stakeholder support was indicated in a species-focused forum.

The recovery team includes representatives from community and natural resource management groups, veterinary representatives, utility organisations, tertiary institutions and State Government departments. The purpose of the team is to facilitate and oversee the implementation of recovery actions with the plan. The team currently is focused on ensuring consistency in monitoring and survey methodologies, identifying and targeting research gaps, supporting on-ground conversation action, ensuring best practice wildlife rehabilitation, and understanding conservation status and trends across the species range.

Projects

Nature Conservation Margaret River Region is a natural resource group operating in the south-west of Western Australia. The group undertakes a number of conservation activities, including a current project focused on conservation actions for the western ringtail possum.

The Oyster Harbour Catchment Group and Torbay Catchment Group are located on the south coast of Western Australia and coordinate natural resource management across Albany and its hinterland. Both groups have projects focused on improving the understanding of the south coast sub-population of western ringtail possum.

Further information

Western Ringtail Possum - EPBC Act SPRAT Profile

Survey guidelines for Australia's threatened mammals. EPBC

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, 2008. Pseudocheirus occidentalis (Ngwayir, Western Ringtail, Western Ringtail Possum)

Woylie

The woylie (Bettongia penicillata ogilbyi) is a small kangaroo-like marsupial. They are also known as brush-tailed bettongs because of the distinctive black brush they have at the end of the long tail. Woylies are nocturnal and forage primarily for underground fungi (native truffles).

Woylies make many diggings in search of the preferred food, and these diggings help water seep into the ground and move nutrients in the soil. Fungal spore survive being eaten by woylies and dispersed around the forest in woylie scats (droppings). As fungi help plants to grow, woylies play an important role in maintaining the health and re-establishment of native vegetation. Woylie are also known to disperse and store seed, which also affects the recruitment and regeneration of vegetation.

The woylie was once hailed as one of the success stories of wildlife conservation programs. In 1996, as a direct result of a recovery program, the woylie was removed from the Threatened Fauna List. However, a dramatic decline in woylie numbers started in 1999 and consequently, the woylie was re-listed in 2008.

This threatened species is listed as Critically Endangered fauna under the Western Australian Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016. Nationally it is listed as Endangered under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, and internationally is on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species as Critically Endangered.

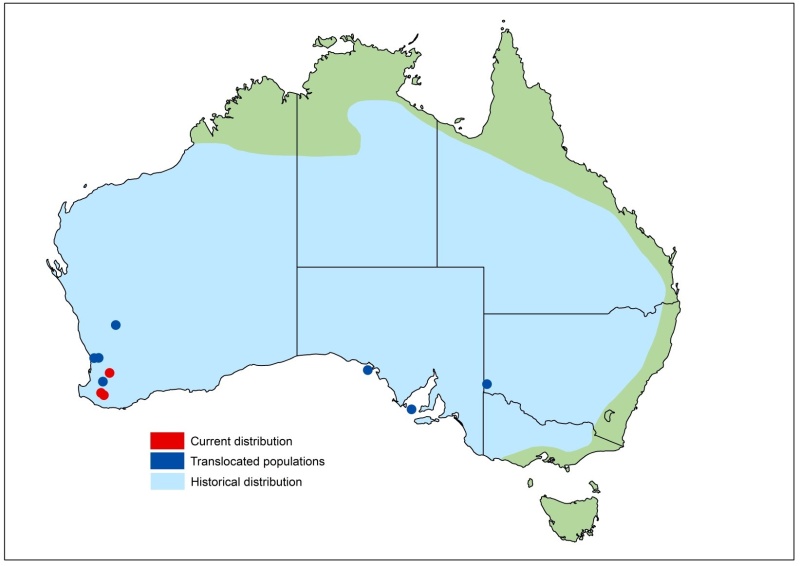

Woylie once occupied most of the Australian mainland south of the tropics including the arid and semi-arid zones of Western Australia, the Northern Territory, New South Wales and Victoria. However, they are now only found in two small areas: Upper Warren and Dryandra Woodland. There are also translocated populations at Batalling and inside fenced areas in Mt Gibson, Karakamia and Whiteman Park, and also in New South Wales and South Australia.

Where woylies are found

Main threats to the Woylie

- Historical habitat clearing for agriculture

- Ongoing habitat loss and fragmentation

- Predation by feral cats and foxes

- Disease and stress

Recovery plan

National recovery plan for the Woylie (Bettongia penicillata ogilbyi). DBCA (2012).

The recovery plan outlines actions that are being implemented to improve the conservation status of the woylie:

- Verifying the causes of decline

- Minimising fox and feral cat predations

- Maintaining the health, genetic diversity and viability of wild populations

- Maintaining genetic health and population sizes of captive populations

- Undertaking translocations, and

- Educating the community about and involving the community in woylie conservation.

Recovery projects

Data gathered through population monitoring provides valuable information to assess the conservation status of the species. There are currently 42 sites throughout the south-west of WA where woylies are monitored. The majority of these sites are part of the department’s Western Shield animal conservation program. The Program controls foxes and feral cats by baiting and monitors some of WA’s most vulnerable native animals, including the woylie, which benefit from predator control.

In 2006, when it became apparent that declines in numbers were continuing and not isolated to a single location, the intensive Woylie Conservation Research Project began. The project is focused on an area east of Manjimup where the greatest amount of information is available, but the project is also gathering information from other locations. It complements the standard fauna monitoring being undertaken through the Western Shield program. The project aims to determine the underlying factors responsible for the recent woylie decline in the Upper Warren region of south-west WA. It is also identifying management strategies required to reverse these declines. You can read more about the project in the Woylie Conservation and Research Project: Progress Report 2010-13 report below.

Woylie demographics are being researched by trapping animals and radio-telemetry has been used to monitor their survival. Food resources, disease and predation have also been the focus of investigations to help identify the possible causes for the woylie decline. Current evidence suggests that woylies have been predated by cats predominantly, but also foxes, and that they may have become more vulnerable to predation by some form of disease. Efforts continue to verify the real causes because knowing for certain is the best way to inform how conservation and management can most effectively save the woylie.

The Perup Sanctuary is a 423 hectare predator-free enclosure in native bushland near Manjimup. It was established in late 2010 as an insurance colony in case the most important woylie populations in the wild became extinct. With a good representation of the genetic diversity of the woylie it is also an excellent source for translocations to help reintroduce the woylie to areas where it is safe to do so. In just the first four years their numbers in the Sanctuary increased from a founding stock of 87 adults to more than 400, plus nearly 300 that have been translocated to three sites to help stimulate their recovery in the wild. More recently, a fenced area has been built at Dryandra Woodland, and woylies are one of the species that will benefit from this predator-free environment.

Key research collaborators with the Department of Parks and Wildlife include Murdoch University, Perth Zoo, Australian Wildlife Conservancy, University of Western Australia, James Cook University, World Wildlife Fund and Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. A major collaborative project with Warren Catchments Council was completed in 2013, with support from the Federal Caring for Our Country and WA State Natural Resource Management programs. Many university students and other partnerships and collaborations have been involved in the efforts to save the woylie. Many university students, volunteers, and other partnerships and collaborations have been involved in the efforts to save the woylie.

If you want to learn more about woylies first hand, visit the Australian Wildlife Conservancy, Whiteman Park and Kanyana Wildlife Rehabilitation Centre websites to find out about tours and volunteer opportunities.